Remember the tagging book drops that were introduced in Chapter 1 as an elegant way to let people add their opinions to library books (page 7)? As I finished writing this book, I decided to solicit a photo to illustrate that story. A Dutch friend agreed to take pictures of the book drops. A month before the book went to press, this email arrived in my inbox (emphasis added):

I am afraid I have got bad news for you… This afternoon I went to the library in Haarlem Oost to take your pictures. When I arrived there, I noticed that they used ‘normal’ returning shelves instead of the tagging system. I asked one of the employees and it turned out that they quit using the system some time ago. Of course I asked her why. She explained that it more or less was a victim of its own success. First of all, particular shelves were overloaded in a short period of time (to be frank, I don’t see the problem here, but to her it was a big problem, so I guess it influenced their working processes).

Next to that, people were using the system so seriously that it took them a lot of time per book to decide where to place it. That caused some logistic problems in the (small) building, especially as they have some peak times. That meant that people often had to wait for other people to return their books – and then once they reached the front, they too needed time to decide where to place their books. There was an alternative system next to the tagging system to improve the flow, but people did not want to be rude and waited patiently on their turn—so the alternative did not work.

The woman I spoke to regrets that they do not use the tagging system anymore. She said that it gave them a good understanding of what the people in the neighborhood like to read. She said that they are determined to introduce the system again when they have a good solution on the logistic problem, but unfortunately she could not give me a concrete term for that.

What happened here? The library introduced a participatory project that proved wildly successful. Visitors liked the activity, and it helped the staff learn more about the usage of the collection. But the book drops failed because they disrupted staff expectations and behavior. The system introduced new challenges for staff—to manage return shelves differently and to deal with queues. Rather than adapt to these challenges, they removed the system.

This doesn’t mean that the librarians at Haarlem Oost were lazy or unsympathetic to patrons’ interests. They were part of an institutional culture that was not effectively set up to integrate and sustain a project that introduced new logistical challenges. They lacked the ability—and possibly the agency—to make the system work reasonably within their standard practices, and so the project became untenable.

Participatory projects can only succeed when they are aligned with institutional culture. No matter how mission-aligned or innovative an idea is, it must feel manageable for staff members to embrace it wholeheartedly. Building institutions that are more participatory involves educating, supporting, and responding to staff questions and concerns. It also requires a different approach to staffing, budgeting, and operating projects. This chapter provides a blueprint for developing management structures that can support and sustain participation, so institutional leaders, staff members, and stakeholders can confidently and successfully engage with visitors as participants.

Participation and Institutional Culture

In 2008, a group of researchers associated with the Online Computer Library Center (OCLC) published a report called Beyond the Silos of the LAMs: Collaboration Among Libraries, Archives, and Museums that reviewed the implementation and outcome of several collaborative projects. The authors noted three frequent reasons why some projects failed to get started or completed successfully:

The idea was not of great enough importance.

The idea was premature.

The idea was too overwhelming.[1]

The first of these is a question of mission relevance, but the second and third relate to institutional culture. Promoting participation in a traditional cultural institution is not always easy. Engaging with visitors as collaborators and partners requires staff members to reinterpret their roles and responsibilities. This can be threatening or uncomfortable for professionals who are unsure how their skills will be valued in the new environment. To successfully initiate a participatory project, staff need to be able to directly address the value, mission relevance, and potential of participation—both for institutions as a whole and for individual staff members.

There are five common issues that arise when pitching or planning a participatory project:

- Some cultural professionals perceive participatory experiences as an unappealing fad. Some people see social networking and related activities as over-hyped, trivial entertainment that will hopefully blow over soon. This perception is exacerbated when well-meaning professionals advocate for engaging on the social Web and in participatory activities because “everyone else is doing it,” using threats of impending irrelevance to prod people into action. While these admonitions may have some truth to them, scare tactics often lead skeptics to become more entrenched in their opposition. Focusing on mission relevance will help these people see the potential value of participation beyond the hype.

- Participatory projects are threatening to institutions because they involve a partial ceding of control. While some other innovative endeavors, like technology investment, have heavy financial risks associated with them, participatory projects need not be expensive to develop or maintain. Instead, they are disruptive to the ways that museum staff members and trustees perceive the image, stature, and content of the institution. To successfully initiate a participatory project, you must be willing to engaging stakeholders in dialogue about the ways participation might diffuse or distort institutional brand and content. Discussing the positive and negative outcomes of visitor participation can help staff members air their concerns and explore new perspectives.

- Participatory projects fundamentally change the relationships between the institution and visitors. If staff members see visitors as a hazy mass of consumers, it will take a lot of work to assert the value of integrating visitors’ voices and experiences into museum content experiences. Additionally, if staff members are not permitted to be personal and open with visitors, they may not be able to facilitate dialogue or manage community projects successfully. To successfully encourage participation, there must be some level of mutual trust and genuine interest among staff members and visitors alike.

- Participatory projects introduce new visitor experiences that cannot be evaluated using traditional museum assessment techniques alone. When talking about the goals of participatory projects, you may find yourself talking about visitor behavior and outcomes that are new to many cultural institutions. Outcomes like empowerment and community dialogue don’t fit into traditional assessment tools used by institutions and funders, which tend to measure outputs rather than impact. Be prepared to educate both managers and funders about alternative ways to frame the goals and outcomes of participatory projects, and to include evaluative tool development as part of the project development process and budget.

- Participatory projects require more staff time and budget allocated for operation than for development. While many cultural institution projects generate products—programs, events, exhibitions, performances—that are released in a completed state and are maintained for a fixed amount of time, participatory projects are released in an “initial” state and then evolve and grow over time. For example, an exhibition that includes heavy visitor contribution on the floor is not “done” until the exhibition closes, and content and design staff members who might have otherwise moved onto other projects after opening may need to continue to manage the project throughout its public run. Make sure your budget and staffing plans match the reality of participatory needs over the course of your project.

Addressing these five concerns should demonstrate how participatory projects are viable at your institution. The next step is to tailor the project’s development to staff culture. Every institution has different strengths and weaknesses that impact which projects are most likely to succeed. If staff members are wedded to long editorial review processes for developing public-facing content, community blogs or on-the-floor contributory projects might not succeed. But that same slow-moving institution might be highly amenable to personalized floor experiences or more long-term community partnerships. Just as each project must fit mission and programmatic goals, it must also be designed to function with pre-existing work patterns in mind.

For example, when the Minnesota Historical Society embarked on the design of the crowdsourced MN150 exhibition, the design team found a way to incorporate visitors’ voices while honoring staff desires to retain control of the overall project. The staff invited citizens to nominate topics for the exhibition, but not much more than that. They didn’t let visitors vote or join in on the topic selection process. They even planned a parallel “Plan B” content development process in case the public nominations didn’t bear fruit (which they did). Once the nominations rained in, senior exhibit developer Kate Roberts reflected:

We locked ourselves in this room with the nominations. We as a team then winnowed based on our criteria—geographic distribution, diversity of experience, topical distribution, chronological distribution, evidence of sparking real change, origination in Minnesota, exhibit readiness, and quality of nomination. We did it with a lot of talking.

A few months later, they emerged with a list of 150 topics and a plan for the exhibition. This project enabled exhibit developers, curators, and designers to start encouraging visitor participation without feeling overwhelmed or uncomfortable.

The MN150 staff and advisor team, deep in deliberation about the topics to be included in the exhibition. At this point, they were vetting a list of 400 nominations that they had sent out to historians, subject experts, and educators for review. Photo courtesy Minnesota Historical Society.

Every institution has some programs or practices about which they are highly protective. It’s important to start with projects that feel safe and open to participation, even if the ultimate goal is to make changes across the institution. For example, while working with a very traditional museum that was trying to start experimenting with participatory engagement with visitors, I proposed a wide range of starting points. We quickly realized that while engaging visitors in dialogue on the Web was acceptable to the staff, giving visitors sticky notes to “mark up” the museum with their questions was not. Though the sticky notes would have taken a fraction of the resources required for the online experiments, curators had two concerns: that the notes would visually degrade the exhibits, and that visitors might ask and answer questions incorrectly, thereby disseminating inaccurate information within the museum. They felt this way despite the fact that the museum had very low visitation and many more people were likely to see the websites than the sticky notes.

In this kind of situation, starting with a tactic that is comfortable for staff can get the conversation moving in a participatory direction. But it’s important to keep pushing the conversation into areas that are less comfortable. At the museum in question, starting on the Web helped staff members feel comfortable, but it also let them separate themselves from participation. They felt like participation was happening “somewhere else” and not on the hallowed ground of the galleries. Our discussions revealed how dedicated they were to creating and controlling the visitor experience in the galleries, and it became clear that it would take concerted effort and a clear strategic vision to move toward engaging in more substantive participatory projects onsite.

Participation Starts with Staff

The best place to start introducing participatory techniques in a cultural institution is internally with staff members and volunteers. If staff members do not feel comfortable supporting or leading participatory projects, these initiatives are unlikely to go far. Like visitors, employees need scaffolding and encouragement to try new things. By educating and including them in the development of participatory projects, you can help staff members feel comfortable and confident with these new endeavors. A participatory institution isn’t just one that is responsive to and interested in visitors’ contributions; it is also one that eagerly and effectively integrates contributions from the staff and stakeholders across the institution.

For example, when the Museum of Life and Science (MLS) in North Carolina started working with social media in a substantive way in 2007, it took a holistic approach that encouraged staff members across the institution to get involved. The MLS hired Beck Tench as Director of Web Experience to lead their efforts. Tench approached individual staff members and stakeholders to see how participatory technologies might support their departmental goals, and she set up small experiments across the institution to help staff experiment with online social engagement and technology.

Horticulture staff members were interested in connecting with people around the unique specimens in the MLS’s plant collection. With Tench’s help, they started the Flickr Plant Project. A horticultural staff member uploads a single image of a rare plant to Flickr once a week along with information about that plant, and then encourages other individuals on Flickr to share their own images and comments of the same plant. Over the first six months of the project, staff uploaded twenty-three images and the project enjoyed 186 user contributions, 137 comments, and 3,722 views. The project design respected the horticulture staff member’s desire to produce very little content while opening up dialogue with people around the world about plants.

In contrast, Tench helped the MLS animal keepers set up a blog to share the behind-the-scenes stories of caring for their often mischievous charges.[2] While at first the animal keepers were skeptical of the project, they were eventually rewarded with a dedicated and eager audience and a new sense of institutional importance. The animal keepers update the blog several times a week with stories, images, and video about their work with the museum’s animals. They also started a “MunchCam,” uploading short videos to YouTube showing how different animals eat.[3]

In addition to online efforts, Tench hosted a weekly happy hour at a local pub, bringing together small groups of staff members each Friday for brainstorming, networking, and relationship-building. In 2009, she ran a personal project called Experimonth in which she chose a monthly goal (i.e., eat only raw foods, do push-ups every day, share a meal with someone every day) and encouraged others—co-workers and friends—to experiment and share the experience using a multi-author blog.

These activities all contributed to a growing sense of the Museum of Life and Science as a safe space for experimentation, even if individuals only opted in to a few discrete opportunities. As Tench put it, “A lot of my work has been just encouraging staff and making them feel that their jobs and reputation will not be threatened through various forms of digital engagement.” By helping staff members find comfortable starting points, she helped make the institution more participatory overall.

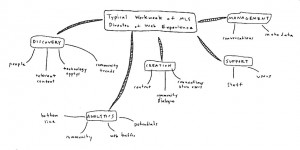

Beck Tench’s visual representation of her work. Despite the title “Director of Web Experience,” she defines her work activities as covering broad topics like discovery, creation, support, management, and analytics. Drawing by Beck Tench.

Changing the Culture

How can staff teams transition from conservative experiments to more significant forays into participation? If you want to pursue a project that may be a true “stretch” for your institution, you need to find deliberate ways to build comfort, encourage staff participation, and provide continual opportunities for feedback and progressive evaluation.

Consider the basic challenge of becoming more responsive to visitors’ interests. I’ve worked with several institutions where staff members have said, “We want to engage in conversation with visitors, but we have no idea where to start.” At these museums, employees who do not work on the front line have little interaction with visitors, and they are often uncertain about who visitors are, why they come, and what interests them. Many staff members may even have a preconceived adversarial relationship with visitors, demeaning their lack of attention and fearing their destruction of the venue and artifacts.

The simplest way to address this is to encourage the staff to spend time working on the front line with visitors. By engaging directly with visitors in low-risk situations, talking to them about exhibits and asking them about their experiences, staff members can start to see visitors as potential collaborators and trusted participants.

Some institutions ask back-of-house staff members to serve as outdoor greeters or help check people in at events. The New York Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) requires all staff members to spend a few hours per month working at the information desk. In MoMA’s case, staff members have remarked that just spending a bit of time answering visitors’ questions helps them keep visitors’ needs in mind when working on other projects. It may not be full-blown participatory engagement, but it’s a start.

Other institutions take this further, encouraging staff members to stay connected to visitors’ needs by leading programs or conducting visitor research. New York’s Tenement Museum, which provides public one-hour tours of historically accurate downtown tenements and the immigrant experience, requires every staff member, no matter how “back of house,” to lead at least one tour per month. This helps everyone stay connected to the institution’s core mission and its visitors.

CASE STUDY: Promoting Institution-Wide Transparency at the Indianapolis Museum of Art

When Maxwell Anderson, the Director of the Indianapolis Museum of Art (IMA), wanted to make his institution more transparent, he knew he had to find a way to involve staff members across the institution in the change. In a 2007 article in Curator, Anderson wrote:

Art museum directors can no longer afford to operate in a vacuum. Transparent leadership requires the disclosure of information that has traditionally been seen as sensitive, such as details on what museums acquire and from whom, how museums attract support and spend it, who they have succeeded in serving, and how they measure success.[4]

To provide more disclosure, the IMA launched an internal project to collect and share data about all aspects of museum operation—how many visitors come from different zip codes, how many pieces of art are on display, how much energy the building consumes each day, and so on. In the fall of 2007, the data was made public on the IMA’s website in an area called the Dashboard.[5] On the Dashboard, visitors can access real-time statistics with information from across the institution. Visitors can access data commonly considered private, such as the real-time size of the endowment, number of staff members, operating expenses, and retail sales.

The Dashboard is a tangible project with several small sub-elements that touch every part of the institution. Everyone, from groundskeepers to registrars, reports their data through a Web-based system to update the Dashboard. Chief Information Officer Robert Stein described the Dashboard this way:

One of our goals was for the Dashboard to reflect the institutional priorities of the museum, and to serve both as an information source for the public, but also as a tracking tool for staff at the museum. If we say energy conservation is important to us, we need ways to track that information over the long term and to monitor whether or not we are being effective. The way the Dashboard works, staff members from around the museum are assigned dashboard statistics which relate to their area of responsibility. These are metrics which are a part of their job responsibilities already. The Dashboard provides a reminder mechanism to keep those statistics fresh, and in context of previous performance. Our goal was to encourage top-of-mind knowledge about statistics we say are important while minimizing the actual data-entry work required to keep up-to-date statistics.

The Dashboard isn’t just for visitors. It’s also a tool that helps build a culture of transparency and participation throughout the IMA. Every time a staff member consciously logs, uploads, and shares data, he participates in the broader institutional effort. Every time a volunteer or museum member logs on to learn more from the Dashboard, she gains a better understanding of the institution that she supports. While not all staff members may like “airing their dirty laundry” on the Web, doing so in such a discrete, tangible, and distributed way helps the whole institution become more comfortable with how the museum is changing. The Dashboard isn’t just a project for the IMA’s Web team. It’s for everyone.

Staff Strategies for Managing Participation

Managing community projects requires a fundamentally different skill set than managing traditional institutional projects. For this reason, many institutions that pursue major participatory projects—whether internally or with outside partners—hire dedicated “community managers” to facilitate them. Community managers may hold positions in community relations, human resources, or strategic planning. Because many participatory projects start on the Web, it’s also common for online managers (like Beck Tench at MLS) to serve in this role.

What makes a good community manager? Community managers need to be skilled at motivating participation and building relationships with diverse participants. Unlike project managers, who are responsible for keeping track of the budget and schedule, community managers are responsible for keeping track of and supporting people. For this reason, community managers’ abilities and unique personalities often have a significant effect on the makeup, attitudes, and experiences of participant populations.

The ideal community manager is someone who connects staff members, volunteers, and visitors to each other in diffuse communities of interest, not a person who engages directly with all participants across all projects. When community managers are the sole masters of visitor engagement, two problems arise. First, their efforts may not be fully integrated into the overall work of the institution, which can lead to conflicts between institutional and community needs. Secondly, the communities they manage often become unhealthily centered on the managers’ personalities and abilities, causing problems when those community managers choose to leave the institution. Healthy communities are not fiefdoms; they’re networks.

Communities can struggle when a single person manages them. When I was at The Tech Museum developing and leading The Tech Virtual community (see page 263), I tried to involve a wide range of staff members in the online exhibit development community so we could spread out the interactions and relationships built between amateurs and experts. Unfortunately, The Tech Museum’s director decided that spending time with participants was a “waste of time” for staff members whose roles were not explicitly focused on that community. The engineers and fabricators who had enthusiastically engaged early on were forbidden to continue participating. Left on my own, I put on my friendliest, most dynamic face and cultivated a couple of volunteers to help manage the growing community of amateur exhibit designers.

I became participants’ sole source of information about the frequently changing project. We started to form unhealthy relationships in which I served as the cheerleader, coach, and point person to all community members. While my energy and enthusiasm as a community leader held the group together, when I left the museum, the community dwindled. Subsequent museum employees have kept the project going, but the community had connected with me as their focal point. There has not been a new person able to comparably rally participants to high levels of involvement.

I don’t tell this story with pride. It was partly my fault that The Tech Virtual community did not thrive beyond my tenure. The system we set up to perform that management and cultivate the community was ill-considered. The project looked good—it kept attracting new members—but it was not sustainable. It’s a warning sign when community members make comments like, “it was only boundless encouragement from Nina that prevented me from giving up more than once.”[6] This participant was one community manager away from leaving the project. It may be easiest to quickly rally a community around one dynamic or charismatic person, but that doesn’t make for a healthy, sustaining project.

Decentralizing Community Management

Why does this happen in the first place? There are two good reasons that organizations tend to focus community activities around a single individual: it consolidates resources spent on a particular strategy, and it simplifies interactions for community members.

Institutions are accustomed to associating individual staff members with specific projects and associated resources. But community managers, like front-line staff, are responsible for interacting with a vast and varied group of people who engage with the institution. They are like development officers who cultivate small, targeted sets of individuals via personal relationships. But they are also the face and voice of the institution to everyone who participates in a project: a front-line army of one. This is a problem. If only one person worked in the galleries of a museum, and he was incredibly charismatic and quirky, his personality would put a unique and specific stamp on the onsite experience—one that might attract some visitors and repel others. The same is true for online and participatory communities.

If an institutional community is focused around one person, staff must plan for succession and think about what will happen if that community manager leaves. Even the most well-intentioned community managers may not be able to transfer their unique personality and style to new staff. Imagine the most popular person in a friend group moving away and trying to anoint a new, unknown person to take her place in the social network—it’s nearly impossible.

The more voices there are in the mix, the more the community management team can effectively welcome community members of all kinds. The Science Buzz blog, which is managed by a team of exhibit developers, science writers, and front-line staff members at the Science Museum of Minnesota, is a good example of diversified community management that models the inclusion of a range of voices and opinions. The Buzz staff representatives even argue with each other in blog comments, modeling a kind of healthy scientific debate that would be impossible for a single community manager to conduct herself.

Strong community managers are educators as well as implementers. They help other staff members understand opportunities for connecting with communities of interest, and they provide support and training so that many individuals across the institution can work with their communities in ways that are sensitive to staff abilities and resources. Consider Beck Tench at the Museum of Life and Science, who helped staff members across the museum start their own participatory projects, including everything from science cafés to animal keeper blogs to exhibits that incorporate visitor feedback. While Tench tracks and supports all of these projects, she’s not the lead on any of them.

The ideal community manager is more like a matchmaker than a ringmaster. He points visitors to the networks of greatest interest to them and helps staff members connect with communities that they want to serve. He is energetic and passionate about serving the needs of the institution’s communities. It’s fine to have a community manager who is the “go to” person—the face of all of the projects—as long as that person is ultimately pointing visitors to other venues for engagement. After all, it’s not desirable for everyone who visits your institution to have a relationship with just one person. Visitors should be able to connect with the stories, experiences, and people that are most resonant to them. A good community manager can make that happen.

Taking a Strategic Approach to Encouraging Staff Participation

Diffusing the institutional voice among multiple staff members can generate confusion for visitors, who may be searching for a single individual to whom they can direct queries. This is a valid concern, especially when community projects are spread across many initiatives or online platforms. For clarity, it is useful to have a single individual as the point person for community engagement. But that person should function as a coordinator and manager of community interactions, not the sole provider of those interactions.

This is as true for both internal and visitor-facing projects. For example, when Josh Greenberg joined the staff of the New York Public Library (NYPL) as Director of Digital Strategy and Scholarship, one of his goals was to “unleash the expertise” of staff librarians and scholars. He encouraged staff members across the institution to engage in community outreach via blogs and other digital projects. The outcome was a slate of new NYPL content channels including blogs, podcasts, and video series about cooking, crafts, poetry, and older patrons’ interests, each written by a different staff member or staff team.[7] By focusing on coordinating and supporting staff rather than producing visitor-facing content, Greenberg was able to effectively manage and inspire an internal community of new digital content producers.

Greenberg is a high-level staff member at NYPL. While community managers don’t have to be at the director or VP level, it is useful for them to be able to think strategically about the overall goals and mission of the organization. High-level community managers are more able to interface with directors across the institution to coordinate reasonable levels of community involvement for various staff members. One of the common challenges of a diversified community management plan occurs when low-level staff members become overly absorbed in community outreach and lose perspective on how those projects fit into their overall job requirements. When community projects are coordinated at a high level, it makes it easier for administrative staff to collectively negotiate and balance different staff members’ involvement.

In the case of the New York Public Library, Greenberg is pursuing a three-phase strategy for encouraging staff involvement in participatory projects:

- Open experimentation. In this phase, the NYPL leadership granted Greenberg permission to work with energized staff members across the library to start blogging and producing digital content. By “unleashing the expertise” of those who were truly invested and engaged, Greenberg’s team was able to start exploring the potential for digital content sharing at NYPL.

- Development of institutional policies. Buoyed by the success of initial experiments, Greenberg began working with other NYPL managers to devise strategies for more widespread staff involvement in digital and community initiatives. Toward that end, he crafted a Policy on Public Internet Communications that put forward an encouraging approach to staff engagement on the Web. By ratifying this policy, the NYPL board indicated that staff could safely initiate digital engagement projects with institutional blessing. Greenberg also worked with the Office of Staff Development to develop new professional development programs to help staff members across the NYPL branches understand how they might use technology to connect with communities of interest around their services and collections. To help the marketing team feel comfortable with diffusing the “voice” of NYPL and to provide consistent and clear expectations for digital engagement, staff members are required to attend one of these training sessions before they can produce digital content on the NYPL website.

- Institutionalization of efforts. This phase is still in the future as of 2010. Greenberg is hopeful that evaluation of digital community engagement techniques, coupled with increased participation throughout the staff, will help NYPL managers see these efforts as core services of the library. Only then can the NYPL integrate expectations for community engagement and digital outreach into hiring practices, job requirements, and policies on staff advancement.

The NYPL is able to take an ambitious and comprehensive approach to digital community engagement due to Greenberg’s leadership. If participation is a strategic goal for your institution, it is useful to have champions at the top who understand what is required from both the management and community engagement perspectives.

Managing Participatory Projects Over Time

The most challenging part of executing participatory projects isn’t pitching or developing them; it’s managing them. Participatory projects are like gardens; they require continual tending and cultivation. They may not demand as much capital spending and pre-launch planning as traditional museum projects, but they require ongoing management once they are open to participants. This means shifting a larger percentage of project budgets towards operation, maintenance, and facilitation staff.

Consider the management of the Weston Family Innovation Centre (WFIC) at the Ontario Science Centre. Sustaining the WFIC requires several different kinds of ongoing content production, maintenance, and support. In one area, visitors can use found materials, scissors, and hot glue guns to design their own shoes, which they can then display informally on a set of plinths throughout the gallery. Supporting this activity requires:

- A continual influx of materials, which are acquired monthly both through donations from local factories and bulk orders

- Exhibit maintenance staff to prepare materials for use each day, which involves tasks such as cutting sponges and fabric, replacing glue sticks, and filling bins

- A WFIC coordinator to sort through each day’s shoes, saving the best examples for showcases and passing the others to maintenance staff for recycling

- Electronics staff to check the glue guns and tools daily to ensure they are safe for visitors’ use

- Host staff to monitor the space, keep bins stocked, and help visitors create, display, and take their shoes home

- Cleaning staff to perform a deep clean of the area each week

The shoe-making activity is highly resource and labor intensive. It is also a high-value, popular activity that has been shown via evaluation to promote the specific innovation skills that the WFIC seeks to support. For this reason, the staff continues to support it, while also seeking ways to make it more efficient.

Other parts of the WFIC have evolved over time to balance their visitor impact with the cost required to manage them. For example, the Hot Zone features video and host-facilitated shows about contemporary science stories. When the WFIC opened, the staff offered five new stories every day. This was incredibly labor intensive, and the staff realized that few, if any, visitors were coming back daily for new content. The team changed their approach and began offering one evolving major story per week, supported by two or three fresh, short daily updates. That way, staff members could present up-to-the-minute content with a reasonable amount of labor.

WFIC staff changed their approach to producing content for shows on up-to-the-minute science news to make the shows more manageable without negatively impacting the visitor experience. Photo (c) Ontario Science Centre 2010.

WFIC manager Sabrina Greupner described running the WFIC as being like running a newspaper. “It involves juggling a list of priorities that changes on a daily basis,” she commented, “and we take a ‘systems’ approach to the effort.” Unlike the other areas of the Ontario Science Centre, the WFIC has dedicated coordinators as well as a dedicated manager. Each morning, the coordinator goes through his area, making a list of prioritized issues to pursue throughout the day. Managers and coordinators focus on the systems and infrastructure needs, which allows hosts to focus on creatively facilitating visitor experiences.

Not every participatory project is as complex as the Weston Family Innovation Centre, but they all require approaches that are different from standard program and exhibit maintenance strategies. Even a simple comment board requires ongoing moderation and organization of visitor content. Developing consistent systems for maintaining, documenting, and supporting participatory platforms can prevent this work from becoming overwhelming. This was the problem that doomed the Haarlem Oost library book drops. The staff didn’t have a good system in place to deal with the shelf overflow and crowding that the tagging activity introduced.

Developing a good system for dealing with participation requires setting boundaries as well as creatively supporting participation. This is particularly true for online community engagement, which can easily extend beyond the workday. While it may make sense for online community staff members to continue to connect with visitors on nights and weekends, managers should help staff develop reasonable boundaries for times when they will not be “on call.” When that information is available to visitors, it helps everyone understand when communication is and isn’t expected.

CASE STUDY: Managing Participation at the San Jose Museum of Art

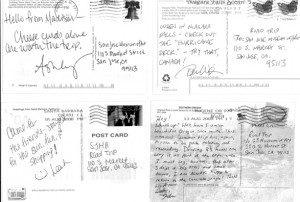

For small museums, setting reasonable boundaries for participatory platforms is essential to their success. For example, in 2008, staff members at the San Jose Museum of Art wanted to create an element for their upcoming Road Trip exhibition that would both promote the exhibition and add an interactive component to the physical gallery. They decided to solicit postcards from real people’s road trips to be displayed in the exhibition. They created a quirky video promoting the postcard project, put it on YouTube, and waited for the postcards to roll in.

What happened? For the first eight weeks, not a lot. There were about 1,000 views of the YouTube video and 20 postcards submitted by August 15th, at which point something strange happened. Manager of Interactive Technology Chris Alexander left work that Friday afternoon having noticed the YouTube view count on the video suddenly rising. By the time he got home, 10,000 new people had seen the video. After some puzzling, he realized that the video had been featured on the homepage of YouTube. YouTube had anointed the Road Trip video with top billing, which shot the views way up (over 80,000 to date) and sent comments and video responses pouring in. The comment stream, which was previously unmoderated, suddenly became overloaded with opportunists who wanted their voice to be heard on the YouTube homepage. Alexander spent an exhausting but rewarding weekend moderating comments and managing the video’s newfound fame.

The attention gained from being featured on YouTube’s homepage prompted an energized burst of postcards from around the world. Overall, the museum received about 250 postcards. They were featured in the exhibition in a little sitting area along with the video and will be kept in the museum’s interpretative archive at the end of the project.

This was a relatively quick project that generated a lot of positive publicity and participation for the museum. But the staff was only able to take it so far. The museum team could not afford to scan or transcribe the postcards, so they were only viewable in the museum, not online. The staff also did not have the time to personally connect with the people who had sent in postcards.[8] This was a one-shot approach—put out the video, collect the postcards. The people who sent in postcards weren’t able to see their content as part of the collection (unless they visited the exhibition in person), and they weren’t recognized for their contribution in a place online where they could both spread the word and enjoy a little fame. This project could not take on a life of its own beyond this exhibition.

The postcards received during Road Trip mostly featured hokey roadside attractions. This was in keeping with the YouTube video, in which SJMA staff visited the World’s Largest Artichoke in Castroville, CA. Photo courtesy San Jose Museum of Art.

From a management perspective, the Road Trip postcard project team made clear decisions about how far they would take their engagement with the postcards. They received, organized, and displayed them, but didn’t digitize them. Even with this self-designated, budget-related constraint, they still ran into management surprises. Alexander gave up a weekend to manage the onslaught of online participation and spam that arrived with the YouTube homepage feature.

The combination of controllable design choices with pop-up surprises is common to many participatory projects. When projects are built to change, staff members must be ready and willing to embrace their evolution.

Sustaining Participation

Many of the projects described in this book are one-time events, programs, or exhibits. How can cultural institutions move from experimenting with visitor participation to integrating it into core functions and services over the long term? To make this happen, staff must be able to demonstrate that participatory techniques help institutions deliver on missions and are appealing and valuable for staff and community members alike.

This can happen from the top down, with new strategic directions focused on the “museum as forum” or the institution as community center. As of 2010, there are several museums and institutional networks reorienting themselves toward community engagement, with staff members at the highest levels publicly advocating for visitor participation and new ways of working. Institutional leadership is essential when it comes to changing institutional culture and fostering supportive environments in which staff can experiment with participation and learn new engagement skills.

But change is also possible from the bottom up. Ultimately, participation succeeds and is sustained not by CEOs and board directors but by the staff and volunteers on the ground. Every institutional stakeholder has a role to play in supporting and leading participatory engagement. Every time a front-line staff member makes a personal connection with a visitor, she builds a relationship. Every time a curator shares his expertise with an amateur, he helps that participant develop new skills and knowledge. Every time a designer develops a showcase for visitors’ contributions, she honors their involvement and creative work. Every time a manager finds a more effective way to maintain a participatory experience, he enables staff members and visitors to keep working together.

Consider the story of Jessica Pigza, a staff member at the New York Public Library (NYPL) who evolved from a rare book librarian into a participatory project leader. Energized by Director of Digital Strategy Josh Greenberg’s open invitation to staff to “unleash their passions,” Pigza started a library blog that focused on handicraft-related items in the NYPL’s collection.[9] The blog slowly attracted a dedicated audience who, like Pigza, were interested in lace making, quilting, and bookbinding.

When Pigza started blogging, she was also teaching a class for general audiences on how to use library collection resources (or, in library-speak, “bibliographic instruction”). These classes were offered in conjunction with the public programming department, and they tended to attract about ten attendees. Pigza realized there was an opportunity to take an audience-centric approach to this outreach and hopefully increase participation by developing a bibliographic instruction class specifically targeted to crafters.

Pigza started offering Handmade, a class for crafters to learn “how library materials can inform and inspire you in your own DIY endeavors.” At the same time, she teamed up with an outside design blogger, Grace Bonney of Design Sponge, to co-create a series of mini-documentaries called “Design by the Book.” The series featured five local artists who came to the library, learned something from the collection, and then went home to make creative works based on their experiences. The videos received tens of thousands of views on YouTube and many enthusiastic comments.[10] The classes and the films inspired a range of new partnerships and effusive responses from crafters.

At that point, Pigza realized, “there was a huge audience of regular, curious people in New York who would love to use the library if they knew they could get access to visual collections and get support from friendly people.” Pigza formed another partnership, this time with Maura Madden, the author of a book called Crafternoon, to offer a series of events called Handmade Crafternoons in which crafters could come learn about the library and make art together.

The Crafternoons were collaborations between Pigza, Madden, and guest artists. Each month, a guest artist would come in to talk about his work, teach a technique, or discuss something from the library’s collection that inspired him. After about thirty minutes of presenting, audience members were invited to socialize, make crafts, and check out collection materials related to the topic at hand.

The free events drew anywhere from 40 to 120 people, many of whom contributed their own materials (as well as financial donations) to share with others during the craft sessions. Crafternoons injected bibliographic instruction with a spirit of collaboration and creativity. Participants approached Pigza with comments like: “I didn’t know I could come into this building,” or “can you help me with research on this personal project related to 1940s women’s knitted hats?” Pigza made new connections with artists, young professionals, and older crafters who started to see the library as a place that supported their community and interests.

At an event in September of 2009, Crafternoon participants made embroidery punch cards, using books from the NYPL collection (including this vintage children’s book) for design inspiration. Photo by Shira Kronzon.

All of these projects were implemented over a matter of months. No one was paid for their time or contributions, including guest artists and collaborators. While the NYPL is moving towards formalizing compensation for participatory projects, they’re not there yet. Ideally staff members and partners would receive compensation for community work, but for now it’s worth it to Pigza and her cohorts to have the opportunity to engage with the craft community through the library. Pigza noted:

My boss knows that I find this to be very satisfying, but he also recognizes that it’s a good thing for the institution in general. He also is one of the people who recognizes the connection between handicraft and history and rare books. I mostly do this work on weekends and nights and days off. It’s not always easy but I have an amazing opportunity to work here and pursue my passion. Not all institutions would support me in this. It’s good for me professionally, and it’s satisfying. I don’t think I’d want to give it up.

The mission of the New York Public Library is “to inspire lifelong learning, advance knowledge, and strengthen our communities.”[11] Pigza’s participatory work with crafters gave her—and the institution—the opportunity to achieve these goals in ways that were previously unimaginable.

When institutional leaders trust their employees’ (and visitors’) abilities to contribute creatively, extraordinary things can happen. No one told Jessica Pigza that craft outreach was outside the purview of her job or that she was overstepping into public programming’s domain. No one told her she couldn’t do her own marketing or form outside partnerships. Instead, her managers encouraged and supported her passions in a mission-specific direction.

Participation becomes sustainable when institutions develop systems to support enthusiastic staff members like Jessica Pigza. It’s a matter of flexibility, focus, and trust. For managers, it’s a question of helping staff members see what is possible, and then developing mechanisms to guide their efforts in the most effective direction. For employees and volunteers, it’s a matter of finding new ways for participatory mechanisms to enhance the value and impact of their work.

There are already people in every institution—managers, staff, volunteers, board members—who want to make this happen. I encourage you to be the one to introduce participatory engagement in your institution. You can do it across a department, with a few colleagues, or on your own if need be. Find a participatory goal that connects to your mission, and develop a way to achieve it. Start small. Ask a visitor a question or invite a volunteer to help you solve a creative problem. Listen, collaborate, test your assumptions, and try again. Soon enough, participation will be a part of the way you do your work, and by extension, the way your institution functions.

***

You’ve reached the end of the strategic section of this book. Now onto the final section, which provides a glimpse of what the future of participatory techniques might hold—a future I hope we can create together.

Chapter 11 Notes

[1] Download and read the Beyond the Silos of the LAMs report by Diane Zorich, Gunter Waibel, and Ricky Erway here [PDF].

[4] See Anderson, “Prescription for Art Museums in the Decade Ahead” in Curator 50, no. 1 (2007). Available online here.

[6] Read Richard Milewski’s longer reflections on my June 2008 blog post, Community Exhibit Development: Lessons Learned from The Tech Virtual.

[8] Note that both of these activities could have likely been performed with the help of volunteers.