Imagine looking at an object not for its artistic or historical significance but for its ability to spark conversation. Every museum has artifacts that lend themselves naturally to social experiences. It might be an old stove that triggers visitors to share memories of their grandmother’s kitchen, or an interactive building station that encourages people to play cooperatively. It could be an art piece with a subtle surprise that visitors point out to each other in delight, or an unsettling historical image people feel compelled to discuss. It could be a train whistle calling visitors to join the ride, or an educational program that asks them to team up and compete.

These artifacts and experiences are all social objects. Social objects are the engines of socially networked experiences, the content around which conversation happens.[1] Social objects allow people to focus their attention on a third thing rather than on each other, making interpersonal engagement more comfortable. People can connect with strangers when they have a shared interest in specific objects. Some social networks are about celebrity gossip. Others center around custom car building. Others focus on religion. We connect with people through our interests and shared experiences of the objects around us.

In 2005, engineer and sociologist Jyri Engeström used the term “social objects” and the related phrase “object-centered sociality” to address the distinct role of objects in online social networks.[2] Engeström argued that discrete objects, not general content or interpersonal relationships, form the basis for the most successful social networks. For example, on Flickr you don’t socialize generally about photography or pictures, as you might on a photography-focused listserv. Instead, you socialize around specific shared images, discussing discrete photographic objects. Each photo is a node in the social network that triangulates the users who create, critique, and consume it. Just as LibraryThing connects people via books instead of reading, Flickr connects people via photos instead of art-making.

The objects don’t have to be physical, but they do have to be distinct entities. Engeström explained object-centered design this way:

Think about the object as the reason why people affiliate with each specific other and not just anyone. For instance, if the object is a job, it will connect me to one set of people whereas a date will link me to a radically different group. This is common sense but unfortunately it’s not included in the image of the network diagram that most people imagine when they hear the term ‘social network.’ The fallacy is to think that social networks are just made up of people. They’re not; social networks consist of people who are connected by a shared object.

This is great news for museums, both in the physical and virtual world. While Web developers scramble for object catalogs upon which to base new online ventures, cultural institutions can tap into pre-existing stories and connections between visitors and collections. And that needn’t happen solely on the Web. Objects can become the center of dialogue in physical galleries as well. This chapter focuses on how to make this possible in two ways: by identifying and enhancing pre-existing social objects in the collection, and by offering visitors tools to help them discuss, share, and socialize around the objects.

What Makes an Object Social?

Not all objects are naturally social. A social object is one that connects the people who create, own, use, critique, or consume it. Social objects are transactional, facilitating exchanges among those who encounter them. For example, one of my most reliable social objects is my dog. When I walk around town with my dog, lots of people talk to me, or, more precisely, talk through the dog to me. The dog allows for transference of attention from person-to-person to person-to-object-to-person. It’s much less threatening to engage someone by approaching and interacting with her dog, which will inevitably lead to interaction with its owner. Unsurprisingly, enterprising dog owners looking for dates often use their dogs as social instigators, steering their pups towards attractive people they’d like to meet.

Take a brief mental tour of your cultural institution. Is there an object or experience that consistently draws a talkative crowd? Is there a place where people snap photos of each other, or crowd around pointing and talking? Whether it’s a steam engine in action or an enormous whale jaw, a liquid nitrogen demonstration or a sculpture made of chocolate, these are your social objects.

Whether in the real world or the virtual, social objects have a few common qualities. Most social objects are:

- Personal

- Active

- Provocative

- Relational

Personal Objects

When visitors see an object in a case that they have a personal connection to, they have an immediate story to tell. Whether it’s a soup bowl that looks just like grandma’s or the first chemistry kit a visitor ever owned, personal objects often trigger natural, enthusiastic sharing. The same is true for objects that people own, produce, or contribute themselves. Recall Click! participant Amy Dreher’s words about her pleasure in visiting the exhibition repeatedly: “I felt ownership over what was on those walls because I had been involved in it.”[3]

Not every artifact automatically stirs a personal response. It’s easy for staff members to forget that visitors may not have personal relationships with many artifacts. Staff and volunteers who care for, study, or maintain objects often have very personal connections with them. One of the challenges for cultural professionals is remembering that visitors don’t come in the door with the same emotional investment and history with artifacts that professionals have and may not see them as obvious conversation pieces.

Active Objects

Objects that directly and physically insert themselves into the spaces between strangers can serve as shared reference points for discussion. If an ambulance passes by or a fountain splashes you in the breeze, your attention is drawn to it, and you feel complicit with the other people who are similarly imposed upon by the object. Similarly, in bars, darts or ping pong balls that leave their playing fields often generate new social connections between the person looking for the flying object and the people whose space was interrupted by it.

In cultural institutions, active objects often pop into motion intermittently. In some cases, like the changing of the guard at Buckingham Palace, the action is on a fixed schedule, and passersby naturally strike up conversations about when it will happen and what’s going on. Other times, the action is more spontaneous. For example, living objects, like animals in zoos, frequently motivate conversation when they move or make surprising sounds. Inanimate objects can also exhibit active behavior—think of the discussions among visitors that naturally arise as model trains chug along their tracks or automata perform their dances.

Provocative Objects

An object need not physically insert itself into a social environment to become a topic of discussion if it is a spectacle in its own right. When the Science Museum of Minnesota opened the exhibition Race: Are We So Different? in 2007, staff frequently noticed crowds of people gathering, pointing, and talking about some of the objects on display. One of the most discussed exhibits was a vitrine featuring stacks of money representing the average earnings of Americans of different races. Money is somewhat exciting on its own, but the real power in the exhibit was in the shocking disparity among the piles. People were compelled to point out of surprise. The powerful physical metaphor of the stacks made the information presented feel more spectacular without dumbing it down or over-dressing it.

Visitors in Race: Are We So Different? discussing the stacks of money demonstrating wealth disparities among different races in the US. Photo by Terry Gydesen.

Provocation is tricky to predict. If visitors expect to be shocked or provoked by content on display—as in some contemporary art institutions—they may choose to internalize provocation instead of discussing it. To work well, a provocative object must be genuinely surprising to visitors who encounter it.

Relational Objects

Relational objects explicitly invite interpersonal use. They require several people to use them to work, and their design often implies an invitation for strangers to get involved. Telephones are relational. Pool tables, seesaws, and game boards fall into this category, as do many interactive museum exhibits and participatory sculptures that invite people to work together to solve a problem or generate an effect. For example, many science centers feature exhibits that explicitly state on their labels, “this exhibit requires two people to use.” One is the player, the other the tracker, or one on the left and the other on the right. These objects are reliably social because they demand interpersonal engagement to function.

Making Objects More Social

Most social object experiences are fleeting and inconsistent. For social object experiences to work repeatedly for a wide diversity of users or visitors, day after day, design tweaks can make an object more personal, active, provocative, or relational. For example, the Museum of Transport and Technology in Auckland has an old traffic light mounted outside one of many small buildings full of artifacts. When staff members put the lights on a timer (red, yellow, green) and painted a street-style crosswalk to evoke a street scene, they were surprised to discover children using the traffic light for spontaneous games of “Red Light Green Light” (or “Go Stop” as it is called in New Zealand). Turning on the lights transformed the traffic light into an active, relational object that was quickly adopted as part of a game.

The Minnesota Historical Society took a different approach in its Open House: If Walls Could Talk exhibition, which opened in 2006.[4] The exhibition tells the personal stories of fifty families who lived in a single house on the East Side of St. Paul over 118 years. Designers used photos and audio recordings to embed personal narratives of residents directly into artifacts in surprising ways. As visitors touch and explore the objects in the house, they unlock personal stories from the people who lived in the house over time. Everything from the dishes to the furniture tells stories. In summative evaluation, researchers found that visitors engaged in high levels of conversation about their connections to the exhibition, with the average visitor relating personal histories to at least three objects on display.[5] By making common household objects personal and active, Open House successfully encouraged people to share their own experiences while visiting.

Physically altering objects is not always the most efficient or practical way to promote social experiences in your institution. It’s often more productive to design interpretative tools and platforms that enhance the sociability of pre-existing objects across the collection. That can mean rewriting labels or placing objects in different environments, but it can also mean more explicitly social approaches to presentation. Jyri Engeström argued that there should be active verbs that define the things users can “do” relative to social objects—consume them, comment on them, add to them, etc.—and that all social objects need to be situated in systems that allow users to share them. To make objects social, you need to design platforms that promote them explicitly as the center of conversation.

Designing Platforms for Social Objects

What makes an interpretative strategy explicitly social? Social platforms focus primarily on providing tools for visitors to engage with each other around objects. While attractive and functional presentation of objects is still important, it is secondary to promoting opportunities for visitors to discuss and share them. Let’s compare the social behaviors supported by a traditional exhibition to those provided by an online social network, Flickr, in the context of the presentation of photographs.

In a traditional museum photo exhibition, visitors can look at photographs hanging on the walls. They can read information about each photo and its creator in label text, and they can probably access information about how the photograph is catalogued in the museum’s collection database. Sometimes visitors may take their own pictures of the photographs; other times, they are prohibited from capturing any likeness of the artifacts or even their labels. In some installations, visitors may be able to share personal thoughts about the photographs in a comment book at the entrance or exit to the gallery. The institution also typically offers visitors the chance to buy reproductions of some of the photographs in a catalogue or postcard set in the museum’s retail shop.

In a typical photography exhibition, visitors can look and learn, but they can’t leave comments or share the images with others as they browse. Social use of the photos is visitor-directed and may or may not be institutionally supported. Photo by Linda Norris.

Contrast these to the visitor actions supported by Flickr. On Flickr, users can look at photos. They can read information about each photo and its creator. They can leave comments on each photo. They can mark particular images as favorites in their personal collections of favorites. They can make notes directly on sub-areas of photos to mark details of interest. They can add tags and geocodes that serve as descriptive keywords for each photo. They can view the comments, notes, and tags created by other users who have looked at each photo. They can send personal messages to each photo’s creator, or to other commenters, with questions or comments. They can invite photographers to submit their photos to special groups or virtual galleries. They can send individual photos to friends by email, or embed them in blog posts or entries on other social networks. They can talk about each photo on Flickr and elsewhere.

Flickr supports a long list of social behaviors that are not available in museums and galleries. This doesn’t mean that Flickr provides a better overall photography exhibition experience. From an aesthetic perspective, it is much more appealing to see photographs beautifully mounted and lit than arranged digitally amidst a jumble of text. When activated, the “notes” function on Flickr deliberately obscures the view of a photo by covering the image in rectangles indicating the locations of noted details. Providing social platforms for objects has design implications that can diminish the aesthetic power of the artifact.

But providing social functions around objects promotes other kinds of user experiences that are also incredibly valuable. Consider this photograph, taken by John Vachon in 1943 and titled “Workers leaving Pennsylvania shipyards, Beaumont, Texas.” In January 2008, the Library of Congress offered this image on the Flickr Commons, a special area of Flickr reserved for images in the public domain.[6] This image is not exhibited at the Library of Congress. If you know what you are looking for, you can hunt it down in the Library of Congress online database via long lists of text.[7] In other words, there was no pre-existing way for visitors to experience this image in a designed context that promoted its aesthetic power or historical significance. Then it was uploaded to Flickr.

But providing social functions around objects promotes other kinds of user experiences that are also incredibly valuable. Consider this photograph, taken by John Vachon in 1943 and titled “Workers leaving Pennsylvania shipyards, Beaumont, Texas.” In January 2008, the Library of Congress offered this image on the Flickr Commons, a special area of Flickr reserved for images in the public domain.[6] This image is not exhibited at the Library of Congress. If you know what you are looking for, you can hunt it down in the Library of Congress online database via long lists of text.[7] In other words, there was no pre-existing way for visitors to experience this image in a designed context that promoted its aesthetic power or historical significance. Then it was uploaded to Flickr.

On Flickr, this photo has an active social life. As of January 2010, it had fifty-three user-supplied tags, eight user-created notes, and seventeen community comments. It was featured by a Peruvian Flickr group called “People—costumes and customs no limits” and another called “Nautical Art.” The image was also shared in an unknown number of blog posts and personal emails sent from the site.

The comments and notes on the Flickr page include several compelling and educational discussions. People answered each other’s questions about why the “Pennsylvania” shipyards were located in Texas. Two people shared personal recollections of growing up near these shipyards, and one added links to historical information about a race riot that happened in the town of Beaumont the same month the photo was taken.

These Flickr users weren’t just saying, “nice pic.” They answered each other’s questions about the content, shared personal stories, and made socio-political commentaries. They did things that are not supported for people who visit the Library of Congress or view the photo in the online database. Flickr arguably supported a more engaging, more educational experience with the content.

Is all of this social value worth the aesthetic tradeoffs that Flickr’s design implies? That depends on institutional goals and priorities. If the goal of the Library of Congress is to encourage visitors to engage with each other about the stories and information at hand, then Flickr is the ideal choice. And similarly, if you want to encourage visitors to engage socially around your content, you should consider ways to build social functionality into exhibits, even if it means diminishing other aspects of the design.

Social Platforms in the Real World

How can you translate the social experience on Flickr to one that is possible for visitors to your institution? You don’t need to replicate every tool provided by sites like Flickr to create successful physical social platforms. You may not be able to write a note directly on an artifact, but museums and physical environments provide other social design opportunities that are impossible to simulate virtually. People use different social tools and transactions in different environments, and not all activities that work virtually translate well to physical environments.

For example, in the real world, oversized objects often function as social objects because they are surprising and can be experienced by many people at once. There’s no way to design a comparable virtual object that suddenly and completely overwhelms several strangers’ sensory experience. Highly designed immersive environments, which provide context that may make some artifacts feel more active or provocative, are another example of a physical design platform that can accentuate the sociality of objects.

The rest of this chapter explores five design techniques that can activate artifacts as social objects in physical design:

- Asking visitors questions and prompting them to share their reactions to the objects on display

- Providing live interpretation or performance to help visitors make a personal connection to artifacts

- Designing exhibitions with provocative presentation techniques that display objects in juxtaposition, conflict, or conversation with each other

- Giving visitors clear instructions on how to engage with each other around the object, whether in a game or a guided experience

- Offering visitors ways to share objects either physically or virtually by sending them to friends and family

Which of these interpretative techniques will work best in your institution? That depends partly on the comfort levels of staff members, but even more so on the comfort level of visitors. Museums can be particularly challenging social object platforms, especially those in which visitors often already feel a little uncertain of how to behave. If visitors don’t feel comfortable and in control of their environment, they are unlikely to talk with a stranger under any circumstances.

Walk around your institution and listen to the hum. Are people naturally and comfortably talking to each other about the objects on display? Do they point things out, pull friends over to share an experience, or engage with strangers? If you work in a very social place, visitors are likely to respond well to open-ended techniques like provocative presentation, questions, and sharing. If your institution doesn’t promote much social activity, then more explicit, directed techniques like instructions and live interpretation might be better starting points.

Asking Visitors Questions

Asking visitors questions is the most common technique used to encourage discussion around objects. Whether via conversations with staff or queries posted on labels, questions are a flexible, simple way to motivate visitors to respond to and engage with objects on display.

There are three basic reasons to ask visitors questions in exhibitions:

- To encourage visitors to engage deeply and personally with a specific object

- To motivate interpersonal dialogue among visitors around a particular object or idea

- To provide feedback or useful information to staff about the object or exhibition

These goals are all valuable, but unfortunately, questions are not always designed to achieve them. Many institutionally-supplied questions are too earnest, too leading, or too obvious to spark interest, let alone engagement. Some questions are nagging parents, asking, “how will your actions affect global warming?” Others are teachers who want parroted answers, inquiring, “what is nanotechnology?” Some pander facetiously. And worse of all, in most cases, there is no intent on the part of the question-asker to listen to the answer. I used to be terrible about this. I’d ask a friend a question, and then I’d get distracted by something else and walk out of the room. I understood the social convention of asking the question, but I didn’t actually care about the answer.

Any time you ask a question—in an exhibition or otherwise—you should have a genuine interest in hearing the answer. I think this is a reasonable rule to live by in all venues that promote dialogue. Questions can create new connections between people and objects and people and each other, but only when all parties are invested in the conversation. Staff members don’t have to be there physically to receive and respond to every visitor’s answer. There don’t even have to be physical mechanisms like comment boards for visitors to share their answers with each other. But the design of each question must value visitors’ time and intelligence, so that answering the question, or entering dialogue sparked by a question, has clear and appealing rewards.

What Makes a Great Question?

Successful questions that prompt social engagement with objects share two characteristics:

- The question is open to a diversity of responses. If there’s a “right answer,” it’s the wrong question.

- Visitors feel confident and capable of answering the question. The question draws on their knowledge, not their comprehension of institutional knowledge.

How do you design a question with these characteristics? There’s a very simple way to test if a question is prescriptive or not, and whether it yields interesting responses: ask it. Take your question out for a spin. Ask it to ten people, and see what kind of responses you get. Pose the question to your colleagues. Ask your family. Ask yourself. Listen to or read the answers you collect. If the answers are different and exciting, you have a good question. If you find yourself dreading asking the tenth person that same question, you have the wrong question.

When designing questions for visitors to answer, I often encourage project teams to get together and write individual questions on pieces of paper and share them around. The staff members then answer each other’s questions personally by writing responses on the sheets. After a few rounds of writing answers on the sheets, the team lines them up and looks at the resulting body of content. This simple exercise can help staff members quickly identify the characteristics of questions that elicit a diversity of interesting responses. It also helps staff members understand what kinds of questions are easier or harder to answer.

There are two basic types of questions that are most successful at eliciting authentic, confident, diverse responses: personal questions and speculative questions. Personal questions help visitors connect their own experience to the objects on display. Speculative questions ask visitors to imagine scenarios involving objects or ideas that are foreign to their experience.

Asking Personal Questions

Personal questions allow visitors to enter the social realm through their own unique experience. Everyone is an expert about himself, and when people speak from personal experience, they tend to be more specific and authentic in their comments. Questions like, “Why is the woman in the painting smiling?” or “What can you figure out about the person who made this object by examining it?” are visitor-agnostic; they are entirely focused on the object. While such questions may encourage people to investigate the object, they are social dead-ends. If your goal is to move towards a social experience, you have to start with a personal question instead.

CASE STUDY: Getting Personal with PostSecret

What’s a secret you’ve never told anyone?

That’s the question behind artist Frank Warren’s PostSecret project. Since 2004, Warren has invited people to anonymously share their secrets by sending him postcards in the mail. He encourages people to make their postcards brief, legible, and creative. PostSecret quickly became a worldwide phenomenon. Within five years, Warren had received hundreds of thousands of postcards. Warren shares a small selection of the ones he receives through his high-traffic blog (named Weblog of the year in 2006),[8] as well as in best-selling books and exhibitions of the postcards.

The success of PostSecret is based on the power of the question, “What is a secret you’ve never told anyone?” It is, by design, one of the most personal questions there is. It’s a question that people are only willing to answer anonymously, and when they do, they generate evocative, haunting responses. As Frank put it, “their courage makes the art meaningful.” The contributors care deeply about their answers, and they labor to create something of value, a worthy vehicle for their secrets. While the postcards may not be aesthetically outstanding, the power of authentic, courageous voices shines through.

The success of PostSecret is based on the power of the question, “What is a secret you’ve never told anyone?” It is, by design, one of the most personal questions there is. It’s a question that people are only willing to answer anonymously, and when they do, they generate evocative, haunting responses. As Frank put it, “their courage makes the art meaningful.” The contributors care deeply about their answers, and they labor to create something of value, a worthy vehicle for their secrets. While the postcards may not be aesthetically outstanding, the power of authentic, courageous voices shines through.

PostSecret has two audiences: Frank Warren and a wide world of spectators and participants. One of the reasons people answer the question is that Warren presents himself as a compassionate, interested listener. He publishes his home address for people to mail in their postcards, which helps establish a relationship of trust and mutual respect between a secret-giver and its recipient. When I heard him speak in 2006, Warren expressed incredible love and appreciation for people who are willing to entrust their secrets to him.[9] But he’s not the only listener out there. PostSecret keeps growing because the question induces a compelling spectator experience. There’s urgency to the secrets—even ones that have been hidden for decades—because each postcard represents the moment at which it was finally let out. And by curating the cards that he releases for mass consumption on the blog and in books, Warren demonstrates which cards that he perceives as most valuable—those that are authentic, diverse, and creative.

Warren commented that he thinks people love the cards not because they’re voyeurs, but because the postcards reveal “the essence of humanity.” I’m not sure that’s true, but there are certainly hundreds of postcards that resonate with me personally—and I imagine with everyone who views them. The PostSecret postcards are social objects that represent an incredible outpouring in response to a simple question framed well by someone who was whole-heartedly ready to listen.

Personal Questions in Exhibitions

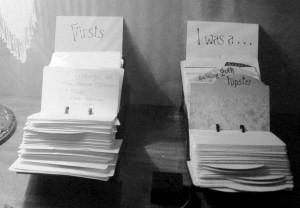

The PostSecret question is incredibly personal, but it is not content- or object-specific (unless you run a Museum of Secrets). If you want to use personal questions to engage people with exhibitions or objects, you need to find a connection between visitors’ lives and the artifacts on display. For example, the Denver Art Museum’s Side Trip exhibition of rock music posters asked visitors to share stories of “my first concert,” “my first trip,” or “the first time I saw… (fill in the musician here).” Another visitor feedback station asked people to reflect on statements like, “I was a roadie,” “I was a hippie,” or “I was not into it.” These were highly personal questions that related to the overall themes of the exhibition and drew compelling, diverse responses. The questions set the stage for interpersonal discussion about individuals’ experience with the music, the lifestyles, and the mythology of hippie culture.

Simple rolodexes allowed Side Trip visitors to share personal stories across a variety of themes. Photo courtesy Denver Art Museum.

Personal questions can also encourage people to be more thoughtful in their engagement with particular objects. In 2007, Exploratorium researcher Joyce Ma published a brief formative study on Daisy, an artificially intelligent computer program that engages visitors in text-based conversation. Daisy is a “chatbot” with some pre-programmed questions in her repertoire, and Ma was studying the ways different questions affected the richness of visitor responses.[10]

In this small study, Ma found that visitors responded at greater length to Daisy when the computer program asked personal questions about the visitors than when it asked about itself. For example, the question, “How do I know I’m talking to a human and not just another machine?” prompted more self-reflection than “Are you sure that I’m not a real person talking to you by e-mail? What would it take to convince you?” The first question focused on the visitor, whereas the second question focused on the object.

Ma also discovered that visitors were more likely to provide elaborated responses when questions were posed in two parts. For example, visitors gave more complex responses to the two-part question: “Are you usually a logical person?” <visitor response> “Give me an example.” <visitor response> than they did to the single question “Are you usually a logical person, or do you let your feelings affect your decisions? Give an example of a recent logical or emotional decision you made.” Simple tasks or questions help build participants’ confidence in their ability to engage in more complicated activities.[11]

This use of personal, progressive questions also elicited highly complex responses in two exhibitions at the New York Historical Society: Slavery in New York (2005) and its successor, New York Divided (2006).[12] These popular temporary exhibitions used artifacts, documents, and media pieces to trace the role of the slave trade in New York City’s history and New Yorkers’ responses to the Civil War. At the end of each exhibition, there was a story-capture station at which visitors could record video responses to four questions:

- How did you hear of the exhibit?

- What was your overall impression?

- How did the exhibit add to or alter your previous knowledge of the subject?

- What part of the exhibition was particularly noteworthy?

Visitors had four minutes to respond to each question, and the story capture experience averaged ten minutes. Richard Rabinowitz, curator of Slavery in New York, noted that the progressive nature of the questions yielded increasingly complex responses, and that “it was typically in response to the third or fourth question that visitors, now warmed up, typically began relating the exhibition to their previous knowledge and experience.” Rabinowitz commented: “as a 40-year veteran of history museum interpretation, I can say that I never learned so much from and about visitors.” It was the lengthy progressive response process that turned what is often a series of brief and banal comments into a rich archive of visitor experience.

The visitor responses to Slavery in New York also demonstrate the power of exhibits and questions that deal with personal impact rather than external visitor opinions. About three percent of visitors to the exhibition chose to record their reactions to Slavery in New York, of whom eighty percent were African-American. This representation was disproportionate relative to the overall demographics of visitors to the exhibition (estimated by Rabinowitz at sixty percent African-American over the course of the exhibition), suggesting that more African-American visitors were moved to share their responses than members of other races. Many visitors explicitly linked the exhibition to their own personal histories and lived experience. A young woman stated she would feel very differently about “returning to work on Wall Street next week, knowing that it was first built by people who looked like me.” One man who visited both exhibitions noted that they changed his perception of “how I fit into the American experience, and the New York experience.”[13]

Another group of young men internalized Slavery in New York in a relational way, saying “After seeing this exhibit I know now why I want to jump you when I see you in the street. I have a better idea about the anger I feel and why I sometimes feel violent towards you.” Chris Lawrence, then a student working on the project, commented:

This visitor addressed the camera as “you,” placing the institution as “white” and to a lesser degree as “oppressor.” This sentiment was not exclusive to teenagers, as many African Americans referenced the New-York Historical Society as a white or European-American institution and took the opportunity to speak directly to that perspective.

These visitors perceived themselves to be in dialogue between “me” the visitor and “you” the museum. The institution responded by posting visitors’ videos on YouTube and integrating clips into the introductory videos that framed both Slavery in New York and New York Divided. By letting visitors “speak first” in a provocative exhibition, the institution demonstrated that it valued their personal experiences as an important part of the dialogue.

Asking Speculative Questions

Personal questions only work when it is reasonable for visitors to speak from their own experiences. If you want to encourage visitors to move away from the world of things they know or experience and into unknown territory, speculative questions are a better approach. You can ask an urban visitor, “what would your life be like if you lived in a log cabin with no electricity?” and she can answer thoughtfully, using her imagination to connect personally with a foreign experience. You can ask an adult, “What would the world be like if you could choose the genetic makeup of your child?” and he can answer without a comprehensive grasp of biochemistry. In cultural institutions, the best “what if” questions encourage visitors to look to objects for inspiration, but not prescriptive answers.

For example, the Powerhouse Museum’s Odditoreum gallery (see page 178) encouraged visitors to look carefully at strange objects and imagine what they could possibly be. The Signtific game (see page 122) asked players to work together to brainstorm potential future scenarios based on scientific prompts. In both cases, people used objects and evidence as the basis for imaginative responses to a speculative question.

CASE STUDY: What if We Lived in a World Without Oil?

Speculative questions don’t have to be off the wall to induce imaginative play states. In 2007, game designer Ken Eklund launched World Without Oil, a collaborative serious game in which people responded to a fictional but plausible oil shock that restricted availability of fuel around the world. The game was very simple: each day, a central website published the fictional price and availability of gasoline, diesel, and jet fuel. The price rose as availability contracted. To play, participants submitted their own personal visions of how they would survive in this speculative reality. People wrote blog posts, sent in videos, and called in voice messages. Many of them created real-world artifacts and documented how the fictitious oil shock was affecting their local gas stations, farmer’s markets, and transportation systems.

Player submissions—over 1,500 in all—were distributed across the Web and networked by the World Without Oil website. Players built on each other’s ideas, intersecting, overlapping, and collaboratively developing a community response to the speculative situation. As one player who called herself KSG commented:

Rather than just getting people to “think about” the problem, it [World Without Oil] actually gets a large and actively interested community of people to throw ideas off of each other through their in-game blog posts, and the out-of-game Alternate Reality Game community. There’s some potential for innovation there, for someone to think up a brilliant lifestyle change for the better that people can start jumping on board with.[14]

The game play motivated people to sample different lifestyles, think differently about resource consumption, and in some cases, change behavior long-term. As another player put it, “We hope that the people who play the game will ultimately live some of what they ‘pretend’ if they don’t already.”[15]

Speculative questions can often seem too silly to couple with serious museum content. But there are many questions like the one posed in World Without Oil that are just close enough to reality to offer an intriguing window into a likely future. What will a library be like when books are a tiny part of their services? Which historical artifacts will resonate from our time? These questions are ripe for cultural institutions to tackle with visitors.

Where Should You Put Your Question?

Once you have a great question in hand, you need to decide how and where to ask it for maximum impact. The most common placement for questions is at the end of content labels, but this location is rarely most effective. Positioning questions at the end of labels accentuates the perception that they are rhetorical, or worse, afterthoughts. To find the best place for a question, you need to be able to articulate the prioritized goals for the question.

Recall the three basic goals for questions in exhibitions:

- To encourage visitors to engage deeply and personally with a specific object

- To motivate interpersonal dialogue among visitors around a particular object or idea

- To provide feedback or useful information to staff about the object or exhibition

If the goal is to encourage visitors to engage deeply with objects, questions and response stations should be as close to the objects of interest as possible. Visitors can speak more comfortably and richly about objects that they are currently looking at than objects they saw 30 minutes earlier in the exhibition.

When these experiences are focused on private, personal responses to objects, enclosed story capture booths such as those used in Slavery in New York are effective. When you want visitors to spend a long time reflecting and sharing their thoughts, it’s important to design spaces for response that are comfortable and minimize distractions.[16] Some projects, like Wendy Clarke’s Love Tapes, even go so far as to let people personalize the space in which they respond to the question. Clarke asked participants to pick a visual background and song to accompany highly personal videos in which they talked about love.[17] This personalization allowed participants to take some control over an emotional and potentially revealing experience.

When the goal is to encourage a large percentage of visitors to respond to questions, visitor responses should be of comparable aesthetics to the “official” institutional content on display. If a label is printed beautifully on plexiglass and visitors are expected to write responses in crayon on post-its, they may feel that their contributions are not valued or respected, and will respond accordingly. One of the things that made the visitor stories contributed in the Denver Art Museum’s Side Trip exhibition so compelling and on-topic was a design approach that elevated visitors’ responses to comparable footing with the pre-designed content. The vast majority of the signage in Side Trip was handwritten in pen on ripped cardboard, which meant that visitors’ contributions (pen on paper) looked consistent in the context of the overall gallery design. By simplifying and personalizing the design technique used for the institutional voice, visitors felt invited into a more natural, equitable conversation.

If the goal is to motivate interpersonal dialogue around an object or subject, the question and answer structure should clearly support visitors building on each other’s ideas. The Signtific game (Chapter 3) did this virtually by encouraging players to respond to each other by “following up” on other players’ entries. You could easily do something similar in a physical space, either by using different color paper or pens for different types of questions and responses, or by explicitly encouraging visitors to comment on each other’s responses or to group their thoughts with like-minded (or opposing) visitor contributions.

If the goal is for visitors to consume each other’s responses, make sure that questions are posed in a location that makes them most useful to others. If you ask visitors to recommend artifacts or exhibits to each other, their recommendations should be on display near the entrance to the galleries, not the exit. The more visitors can see how their voices add to a larger, growing conversation, the more likely they are to take questions—and their answers—seriously.

Finally, if the goal is for visitors to provide useful feedback to staff, the question station must make its utility clear to visitors. In 2009, the Smithsonian American Art Museum launched Fill the Gap, a project in which visitors were invited to suggest which pieces of art might be used to fill vacancies left in the public display when pieces went out on loan or into conservation labs. Visitors could answer in-person by writing on a comment board at the museum, or they could answer online via a Flickr-based version of the project.

The Fill the Gap activity station clearly communicated a simple, meaningful question. Photo courtesy Luce Foundation Center.

The question, “What object would fit best in this spot?” is not a particularly sexy question, but it began a meaningful conversation between staff members and visitors. The institution clearly indicated that staff would listen to and act on visitors’ responses. The activity required visitors to carefully examine objects and to advocate for their inclusion by making arguments in a distributed conversation among visitors and staff members. Importantly, the results of the conversation were visible—visitors could return and see which object had been selected and inserted into the gap. Visitors engaged with the objects to answer the question because they understood how it would provide value to the institution.

Tours and Facilitated Social Experiences

While questions may be the most common technique, the most reliable way to encourage visitors to have social experiences with objects is through interactions with staff through performances, tours, and demonstrations. Staff members are uniquely capable of making objects personal, active, provocative, or relational by asking visitors to engage with them in different ways. This section does not focus on the many fabulous ways that live interpretation helps people understand and experience the power of museum objects, but instead looks specifically at ways interpretation can make the visitors’ experiences more social.

Making Tours and Presentations More Social

What does it take to make a tour or object demonstration more social? When interpreters personalize the experience and invite visitors to engage actively as participants, they enhance both the social and educational value of cultural experiences. Demonstrations that involve “guests from the audience” or encourage small groups of visitors to handle objects allow visitors to confidently connect with objects in a personal way. Staff members who ask meaningful questions, give visitors time to respond, and facilitate group conversations can make unique and powerful social experiences possible.

In a 2004–6 study at Hebrew University’s Nature Park, researchers found that even a few minutes of personalization at the beginning of a tour can enhance visitors’ overall enjoyment and learning.[18] A Discovery Tree Walk guide was trained to start her tour with a three-minute discussion about visitors’ personal experiences and memories of trees. She then lightly wove their “entrance narratives” into the tour itself. Compared to a control group (with whom she chatted casually before the tour, but not about trees), the group who received personalized content was more engaged in the tour and rated the experience more positively after it was over.

In some programmatic experiences, visitors are explicitly encouraged to act like researchers and to develop their own theories and meaning around objects. In the world of art museums, the Visual Thinking Strategies (VTS) interpretative method, developed by museum educator Philip Yenawine and cognitive psychologist Abigail Housen in the late 1980s, is a constructivist teaching technique used to encourage visitors to learn about art by engaging in dialogue with the art itself. VTS is simple on the surface. Facilitators use three basic questions: “What’s going on in this picture?,” “What do you see that makes you say that?,” and “What more can we find?” to lead discussion. Staff members listen carefully, rephrase visitors’ comments to validate their interpretations, and use the three questions to keep the conversation going.

Unlike traditional museum art tours, VTS facilitators do not provide historical context for the works discussed; in most cases, facilitators don’t even identify the artist or the piece. The point is not for the guide to confer knowledge, but to encourage visitors to think openly, vocally, and socially about what art means and how it works. Several research studies have demonstrated that students in VTS programs increased their visual literacy, critical thinking skills, and respect for others’ diverse views.[19] By encouraging visitors to talk through their observations, VTS models a kind of dialogue that visitors can continue to employ outside of the facilitated experience.

Provocative Programming

Just as a provocative object can spark dialogue, a provocative staffed experience can give visitors unique social experiences.[20] Perhaps the most famous provocative visitor tour is that in Dialogue in the Dark (DITD), an international traveling exhibition that has been experienced by over 6 million visitors in 30 countries since it opened in 1988. DITD is a guided experience in which visitors navigate multi-sensory simulated environments in total darkness. Their guides are blind people. The experience is intensely social; visitors rely on the guides for support as they move into confusing and potentially stressful scenarios like a busy street scene or a supermarket.

The social experience of DITD frequently results in sustained visitor impact. In exit interviews, visitors consistently talk about the emotional impact of the experience, their newfound appreciation for the world of the blind, and their gratitude and respect for their blind guides. In a 2005 study of 50 random visitors who had attended DITD in Hamburg, Germany in the year 2000, one hundred percent remembered the experience, and 98% had talked about it with others. Sixty percent changed their attitude towards blind people, and 28% self-reported changing their behavior towards people with disabilities.[21] A 2007 study of forty-four blind guides at six European DITD venues showed that their work with DITD led to increased self-confidence, communication skills, and enhanced relationships with friends and family.[22]

While the setting for Dialogue in the Dark is intense and unusual, the social experience is safe and supportive. By contrast, the Follow the North Star experience at Conner Prairie, a living history site in Indiana, combines a bucolic natural setting with a stressful social experience. Follow the North Star is a role-playing experience that takes place in 1836. Visitors portray a group of Kentucky slaves who try to escape while being moved by their owners through the free state of Indiana. In contrast to the common interpretative technique in which staff members portray characters and visitors are observers, Follow the North Star puts the visitors in the middle of the action as actors themselves. As historian Carl Weinberg described it, “As visitors, we are not only performing ‘old-timey’ tasks. We are central actors in a drama, taking on a whole new identity, as well as the risks that identity entails.”[23]

This approach leads to powerful interpersonal experiences among visitors in a group. Visitors may be pitted against each other or forced to make decisions about which of them should be sacrificed as bargaining chips with costumed staff members along the way. Hearing a fellow visitor yell at you to move faster can be much more intense than hearing it from a staff member who you know is paid to act that way.

All groups are debriefed after the reenactment is over, which often prompts interpersonal dialogue among visitors. Guest Experience Manager Michelle Evans recounted one particularly heated debriefing:

A mixed race group began their debriefing on a tense note. After a white participant spoke about his experience, a black woman commented, shaking her head, “You just don’t get it.” But this fortunately opened up such an engaging conversation that the whole group headed to Steak and Shake afterward to continue to the discussion.[24]

Designing experiences like Follow the North Star is incredibly complex. You have to balance the intensity of the planned experience with the social dynamics of strangers working in groups. I was the experience developer for Operation Spy at the International Spy Museum, a guided group experience in which visitors portrayed intelligence officers on assignment in a foreign country on a time-sensitive mission. In the design stage, we constantly weighed the desire to have visitors work together against their hesitancy to do so in a high-stakes environment in which each wanted to perform as well as he or she could individually. As in Follow the North Star, we had to balance visitors’ desires to discuss the experience with the need to keep the story (and the energy) moving. The Operation Spy guides are part actor, part facilitator, and it isn’t easy to maintain dramatic intensity while managing visitors’ interpersonal and individual needs.

CASE STUDY: Object-Rich Theater at the Indianapolis Children’s Museum

Follow the North Star and Operation Spy are expensive, complicated productions to design and facilitate. But it is also possible to integrate live theater experiences into exhibition spaces, more naturally connecting visitors to important objects and stories.

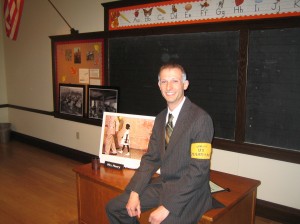

One of the best examples of this is in The Power of Children permanent exhibition at the Indianapolis Children’s Museum. The Power of Children features the stories of three famous courageous children throughout history: Anne Frank, Ruby Bridges, and Ryan White. Three spaces in the exhibit can transition from open exhibit space to closed theater space via a couple of strategically placed doors. There are several ten-to-fifteen-minute live theater shows in the exhibition per day, each of which features a single adult actor. I watched one of the Ruby Bridges shows in an exhibit space designed to simulate the classroom in which Bridges took her first grade classes alone. She spent a year going to school by herself because all the white parents chose to remove their children from school rather than have them contaminated by an African-American classmate.

The Ruby Bridges show treated visitors like participants, not just passive audience members. In the show I experienced, a male actor portrayed a US marshal reflecting on his time protecting Bridges as she walked to school. The actor used objects (photos from the time, props in the room) and questions to connect us with the story and the real person. The choice to use an adult actor who was both a fictitious “insider” to the story and a “real life” outsider like the rest of the audience enabled him to facilitate personal connections among us as a community of observers to the story. We could relate to the personal conflict he was expressing, and he treated us as complicit partners, or confessors, to his experience. Visitors weren’t asked to BE Ruby Bridges—instead, we were treated like citizens of her time, scared, confused, uncertain.

The show also explicitly connected us to the objects in the room. We were sitting on the set—in classroom desk chairs facing him at the blackboard. The whole show allowed us to live in the imaginative space of Bridges’ classroom. What if I was the only student in my class? What if people yelled horrible things at me on my walk to get here every day?

This show didn’t separate visitors from the action. It let us onto the stage to share it with the actor, the objects, and the story at hand. And when the show was over, we got to stay onstage. Because the room was both an exhibit space and a theatrical space, visitors could continue to explore it after the show was over. Visitors could connect with the artifacts and props in the space without being rushed out, and there were opportunities to discuss the experience further with the actor and other audience members.

The actor portraying the US marshal delivered his show inside this classroom. The print on the desk and photos in the background are both historic props used to connect visitors to the real story of Ruby Bridges.

In contrast, there are many painful museum theater experiences that seemed to willfully ignore visitors’ desires to participate or engage with each other socially. On a 2009 trip to the National Constitution Center, I joined a small group of visitors for a live theater show about contemporary issues related to constitutional law. Four actors presented a series of vignettes and then concluded by asking us to vote by raising our hands to indicate how we would have decided in each of the cases. There were only ten of us in the audience, and as we dutifully raised and lowered our hands, it was painfully obvious that we could have had interesting dialogue about our different opinions on the issues. Instead, we were thanked, given surveys, and shuttled out. As a small group of adults, it felt condescending and almost bizarre to sit silently through a long show by four actors when they could have easily prompted discussion.

Facilitating Dialogue Instead of Putting on a Show

When staff members are trained to facilitate discussion rather than deliver content, new opportunities for social engagement emerge. When the Levine Museum of the New South mounted a temporary exhibition called Courage about the early battles for school desegregation in the United States, they accompanied the exhibition with an unusual programming technique called “talking circles.” This Native American-derived dialogue program invited visiting groups to engage in facilitated discussion about race and segregation in an egalitarian, non-confrontational way. The Courage talking circles were designed for intact groups—students, corporate groups, civic groups—and have become a core part of how the Levine Museum supports community dialogue and action based on exhibition experiences. When the Science Museum of Minnesota mounted their Race exhibition, they also used the talking circle technique with local community and corporate groups to discuss issues of race in their work and lives after viewing the exhibition.

Learning to facilitate dialogue is an art.[25] While there are entire books written on the topic, the general principles are the same as those for designing civic participatory environments. Respect participants’ diverse contributions. Listen thoughtfully. Respond to participants’ questions and thoughts instead of pushing your own agenda. And provide a safe, structured environment for doing so.

Provocative Exhibition Design

Live interpretation is not always possible, practical, or desired by visitors. Even without live interpreters, there are ways to design provocative, active settings for objects that can generate dialogue. Just as dramatic lighting can give objects emotional power, placing objects in “conversation” with each other can enhance their social use. When visitors encounter surprising design choices or objects that don’t seem to go together, it raises questions in their minds, and they frequently seek out opportunities to respond and discuss their experiences.

Provocation through Juxtaposition

One of the most powerful and simple ways to provoke social response is through juxtaposition. Rarely employed in online platforms, juxtaposition of artifacts has been the basis for several groundbreaking exhibitions, including Fred Wilson’s Mining the Museum, presented in 1992 at the Maryland Historical Society. Wilson selected artifacts from the Historical Society’s collection—objects that were overlooked or might have been perceived to have little evocative power—and used them as the basis for highly provocative, active, relational exhibits. He placed a fancy silver tea set alongside a pair of slave shackles, paired busts of white male statesmen with empty nameplates for African-American heroes, and contrasted a Ku Klux Klan robe with a baby carriage.

While the objects in Mining the Museum were (for the most part) unremarkable, the platform on which they were presented added a provocative, relational layer to their presentation. This translated to a more social reception by visitors. Juxtaposition implies obvious questions: “Why are these here and those missing?” “What’s going on here?” Curators and museum educators often ask questions like this, but these questions can fall flat when presented as teachable moments. In Mining the Museum, these questions were not explicit but bubbled naturally to the top of visitors’ minds, and so people sought out opportunities for dialogue.

Mining the Museum generated a great deal of professional and academic conversation that continues to this day. But it also energized visitors to the Maryland Historical Society, who engaged in dialogue with each other and with staff members, both verbally and via written reactions, which were assembled in a community response exhibit. Mining the Museum was the most well-attended Maryland Historical Society exhibition to date, and it fundamentally reoriented the institution with respect to its collection and relationship with community.

Several art museum exhibitions have paired objects in a less politicized way to activate visitor engagement. In 1990, the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden mounted an exhibition called Comparisons: An Exercise in Looking in which pairs of artworks were hung together with a single question in-between. By asking visitors to connect two artifacts via explicitly relational queries, the artworks were activated as social objects in conversation with each other. The questions were subjective, but they all encouraged deep looking. Some were open-ended: “Do you respond more to one work than the other?” whereas others were more educational: “Is it apparent that Liger has changed the composition and painted over areas in either painting?”

From interviews with ninety-three visitors, researchers determined that visitors primarily considered Comparisons to be an “educational gallery” and that they wanted to see more such exhibitions. One visitor comment noted that the exhibition was very interesting, but “definitely an exhibit to see with someone.” Another visitor observed: “(married) couples had wonderfully disparate views as they saw this exhibit.” The questions provided tools for discussion in a venue in which visitors often feel uncertain about how to respond to objects on display.[26]

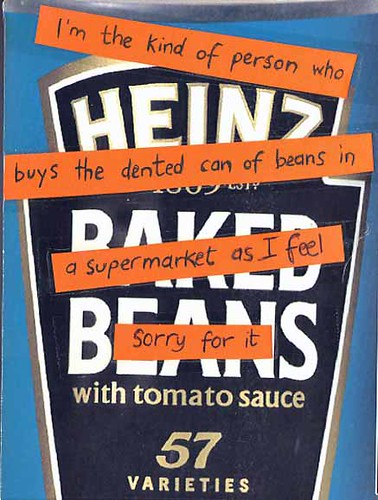

In 2004, the Cantor Art Center at Stanford University took this idea further and presented Question, “an experiment that provokes questions about art and its presentation in museums.” Rather than just displaying art in a neutral way along with questions on labels, Question featured radical display techniques that were intended to explore but not answer basic questions that visitors have about art, like “What makes it art?,” “How much does it cost?,” and “What does it mean?”

Is it art if my kid could draw that? Question employed unusual display techniques to encourage discussion and debate. Photo by Darcie Fohrman.

The team mounted artworks by famous artists and children together on a refrigerator. They crowded European paintings against a cramped chain-link fence and mounted other pieces in natural settings with sound environments and comfortable seating. All of these unusual and surprising design techniques were meant to provoke dialogue. As exhibit designer Darcie Fohrman commented, “In the museum field, we know that learning happens when there is discussion and conversation. We want people to ask strange questions and say, ‘I don’t get this.’”

In summative evaluation, researchers found that 64% of visitors discussed exhibit content while in the gallery, which was high relative to typical visitor behavior. Visitors spent twice as much time at exhibits whose labels led with a question than those that did not, and that the interactive or provocative exhibits were more likely to generate conversation than their more traditional counterparts. In addition to verbal conversation, visitors frequently responded to each other through text-based participatory exhibits. For example, the entry to Question featured two graffiti walls with peepholes through which people could look at artworks and write up their own questions and responses about art. The walls proved so popular they had to be repainted multiple times over the run of the exhibition.

Provocation through Fiction

Fred Wilson didn’t just place objects in dialogue with each other; he also wrote labels and interpretative material that deliberately twisted the meaning of the artifacts on display. Artist David Wilson uses a similar technique at the Museum of Jurassic Technology in Los Angeles, which showcases very odd objects alongside labels that couple an authoritative tone with fantastical content. These artists play games with the ways cultural institutions describe and attribute meaning to artifacts in museums. By doing so, they invite visitors to question what’s going on in an exhibition or institution.

CASE STUDY: Imaginative Object Descriptions at the Powerhouse Museum

Playing games with objects isn’t just a high art technique; it can also help visitors construct their own meaning about objects and have some fun while doing so. In the summer of 2009, the Powerhouse Museum opened a temporary gallery called the Odditoreum, which presented eighteen very odd objects alongside fanciful (and fictitious) labels written by children’s book author Shaun Tan and schoolchildren. While the Odditoreum was designed for families on holiday, the Powerhouse described it as being about meaning making, not silliness. The introductory label talked about “strangeness, mystery, and oddity” and noted that, “when things are strange, the brain sends out feelers for meaning.” This is a powerful statement that encouraged visitors to think about the “why” of these objects.

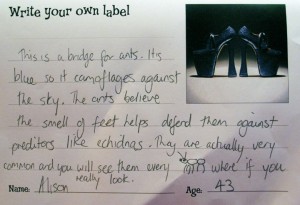

The Odditoreum featured a participatory area in which visitors could share their reactions by writing their own labels to go with the bizarre objects on display. This component was very popular and well used, and the visitor-submitted labels in the Odditoreum were inventive and on-topic.

While many museums have experimented with “write your own label” campaigns, the Odditoreum was unique in its request that visitors write imaginative, not descriptive, labels. While many visitors may feel intimidated by the challenge to properly describe an object, everyone can imagine what it might be. The speculative nature of the exhibition let visitors at all knowledge levels into the game of making meaning out of the objects. And yet the imaginative activity still required visitors to focus on the artifacts. Every visitor who wrote a label had to engage with the objects deeply to look for details that might support various ideas and develop a story that reasonably fit the object at hand.

The Odditoreum was carefully designed to encourage imaginative play without asking visitors to also absorb the “correct” story of each object. The Powerhouse team dealt delicately with the presentation of the “real” information about each object. As Public Programs Producer Helen Whitty put it: “I didn’t want the fantasy label immediately next to the real information, thus spoiling the approach (‘really you thought we were going to have fun but really it’s business as usual’).” Instead, the museum mounted the real information (“What they actually are!”) together on one large panel nearby—available, but not the point of the experience.

In all of these examples, design techniques were strategically optimized to promote artifacts as objects of conversation. The objects were not presented in a way that allowed visitors to receive the most accurate information or the most pleasing aesthetic experience. It’s hard to take pleasure in a silver tea set that is forcibly paired with a set of slave shackles, and a refrigerator is probably not the ideal aesthetic setting for a sketch by Miró. By designing the exhibitions as successful social platforms, these exhibitions drew in new and enthusiastic crowds, but they also turned off some visitors for whom the approach was unfamiliar and unappealing. Just as Flickr’s choice to allow users to write notes on photos may be distracting to some photography buffs who prefer unadulterated images, socializing exhibition techniques introduce design tradeoffs that may be in conflict with other institutional values or visitors’ expectations.

It’s no coincidence that these kinds of projects typically involve outside artists or designers. Even if doing so might invite visitors to spend time discussing and exploring the objects intently, staff members rarely give themselves permission to display objects in ways that might be seen as denigrating their worth or presenting false information about their meaning. If you want to present objects in a provocative setting, you must feel confident—as did each of these design teams—that social response is a valuable and valid goal for visitor engagement.

Giving Visitors Instructions for Social Engagement

The easiest way to invite strangers to comfortably engage with each other is to command them to do it. Provocative presentation techniques, even when overt, can be misinterpreted. If you are looking for a more direct way to activate artifacts as social objects, consider writing some rules of engagement with or around the objects.

This may sound prescriptive, but it is something museum professionals are already comfortable with when it comes to individual experiences with interactive elements. Instructional labels explain step-by-step how to stamp a rivet or spin the magnet. Audio tours tell visitors where to look. Educators show people how to play. Many games and experiences use instruction sets as a scaffold that invites visitors into social experiences that become much more open-ended and self-directed.

Exhibits that require more than one person’s participation typically employ labels that say, “sit down across from a partner and…” or “stand in a circle around this object.” For visitors who arrive with family or social groups (the majority of museum visitors), these instructions are easy to fulfill. But for solo visitors, these labels pose a challenge. Where can I find a partner? How can I get others to stand in a circle with me?

For solo visitors, it’s easiest to engage if labels explicitly instruct people to “find a partner,” or, even better, to “find someone of your gender,” or “find someone who is about your height.” Specific instructions give visitors comfortable entry into social encounters that would otherwise feel awkward. A visitor can point back to the instruction label and say to a stranger, “it says I need to find another woman to use this exhibit.” The stranger can confirm via the label that this is indeed an institutionally sanctioned interaction. And if the stranger declines to participate, she isn’t rejecting the asker—she’s rejecting the instruction. It’s not that she finds something unsuitable about the other visitor; she just doesn’t want to play the game. Clear instructions give both askers and respondents safe opportunities to opt in and out of social experiences.

CASE STUDY: Taking Instructions at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art

In some traditional institutions, especially art museums, it can be hard to convince visitors that it is okay to engage directly with the objects, let alone with each other. When the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA) mounted The Art of Participation in 2008, the exhibition included several components in which visitors were explicitly instructed to interact with objects and with each other. Recognizing how unusual these activities were in the face of standard art museum behavior, SFMOMA used orange label text for all of the interactive components. At the entrance to the exhibition was a simple orange label that read:

Some of the objects in this exhibition are documents of past events, but others rely on your contribution. Watch for the instructions printed in orange on certain object labels—these signal that it is your turn to do, take, or touch something.

In other words, SFMOMA created a special label type for interactive elements. This label set up a casual game for visitors inclined towards participation: look for orange text, do the activity. Had the participatory instructions been integrated into the standard black text labels, visitors might not have be as aware of the commonalities across the interactive art pieces. The repetition of the orange may also have encouraged some reluctant visitors to engage later in their visit, as it suggested multiple opportunities for participation.

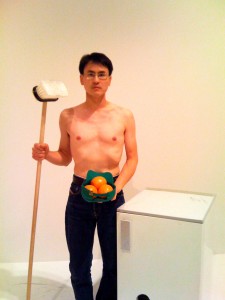

I had a powerful social experience in The Art of Participation with the interactive One Minute Sculptures by artist Erwin Wurm. The artwork was a low, wide stage in the middle of the gallery with some unusual objects on it (broomsticks, fake fruit, a small fridge) and Wurm’s handwritten instructions encouraging visitors to balance the objects on their bodies in funny, specific ways. About three people could fit on the stage comfortably, and the evocative, weird instructions naturally led people to try their own combinations of objects and positions.

The orange label for this artwork read:

Follow the artist’s instructions. Take a picture of your One Minute Sculpture and post it to the SFMOMA blog (www.blog.sfmoma.org) Use the tag “SFMOMAparticipation” to help others find it.

Emboldened by this label, I gave my phone to a stranger and asked him to take my picture. He took a picture of me balanced on the fridge and then suggested that I try a slightly different pose. Soon, we were cheerfully art-directing each other into increasingly strange poses. We enticed onlookers to join us and gave them explicit instructions about how to pose with the objects.

The gallery turned into a group social experience in the creation of art. I knew something unusual and powerful was happening when, several minutes into this experience, my new friend George paused mid-pose and said, “I think I’m going to take off my shirt.”

I don’t often meet people in art museums who spontaneously undress. This was an incredible social experience mediated by the objects on display. It was unique; I don’t expect to experience this kind of playfulness, intellectual curiosity, and physical intimacy with every visitor with whom I engage socially in museums.

But it need not be an isolated incident. The me-to-we pattern was at work—George and I each engaged first with the exhibit individually. We read specific instructions and then adapted them to create personal expressions of self-identity. The exhibit platform was well positioned and designed to naturally draw in spectators and would-be participants. There was a direct prompt to take pictures of each other (a simple social action). There was also the space and opportunity for the exhibit to encourage open-ended and truly wild social art experiences. What started with clear instructions turned into a strange and memorable event.

Giving Instructions via Audio

As a further exploration of the use of instructions in motivating social experiences, consider the audio guide. Traditional audio guides use instructions to help visitors orient themselves, but some artists have used this medium to great effect to encourage visitors to have surprising, social experiences. This section compares two such audio experiences: Janet Cardiff’s Words Drawn on Water (2005) and Improv Everywhere’s MP3 Experiments (2004–ongoing). These experiences were both offered for free. They were both about 35 minutes in length. They took place in major cities—Washington, D.C. and New York City, respectively. But they had very different social outcomes.

In 2005, the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden commissioned sound artist Janet Cardiff to create a 33-minute audio walk, Words Drawn on Water, around the National Mall in Washington, DC.[27] Visitors put on earphones and listened as Cardiff told them exactly where to go, step by step. Words Drawn on Water used a combination of exacting directions and fictional narrative to draw participants into a series of intimate object experiences. It was a highly isolating, personal experience. Cardiff layered strange sounds—bees zooming in, soldiers marching—over a journey through museums and sculpture gardens, and she interpreted objects like James Smithson’s tomb and the Peacock Room in the Freer Gallery in an evocative, dreamlike way. Though I experienced it with friends (and we talked afterwards), throughout the audio walk each of us was lost in the minutiae of her own augmented experience.

By contrast, Improv Everywhere’s MP3 Experiments are designed to encourage social experiences, not personal ones.[28] Like Cardiff, Improv Everywhere distributes audio files for people to listen to on their own personal audio devices while navigating urban environments. The MP3 Experiments are event-based. Participants gather in a physical venue at a prescribed time with their own digital audio players, and everyone hits “play” at the same time. For about half an hour, hundreds of people play together silently, as directed by disembodied voices inside their headphones. The city becomes their game board, and everyday objects are activated as social game pieces. Participants point at things, follow people, and physically connect with each other. They use checkerboard-tiled plazas as boards for giant games of Twister. The MP3 Experiments are a model for how a typically isolating experience—listening to headphones in public—can become the basis for a powerful interpersonal experience with strangers.

What made Words Drawn in Water a personal experience and the MP3 Experiments social? The difference is in the audio instructions. In both Words Drawn on Water and the MP3 Experiments, the audio track overlays unusual instructions and suggestions onto a familiar landscape. But Cardiff layered on strange and surprising narrative elements that confused and unsettled listeners. This confusion made visitors ask themselves: Where am I? Is there really a bee in my ear? Why is she saying I’m in England? As the audio piece continued, listeners followed specific instructions on where to step, but they were also immersed private worlds of strange, secret thoughts.

The MP3 Experiments added a layer of silliness and play, not story and mystery, to the instructional set. Unlike the step-by-step instructions in Words Drawn on Water, which made you feel as though you had to keep up or it might leave you behind, the MP3 Experiments were scripted to make participants feel comfortable, giving them lots of time to perform tasks and rewarding them energetically for doing so.

Participants in MP3 Experiment 4 take photos of each other, following the instructions provided by their digital audio devices. Photo by Stephanie Kaye.

Deconstructing just the first few minutes of an MP3 Experiments audio piece reveals a lot about what makes this project so successful as a social experience. Here’s a breakdown of the first five minutes of MP3 Experiment 4 (2007):[29]

- 0:00–2:30: Music.

- 2:30–4:00: Steve, the omnipotent voice, introduces himself. He explains that you will have to follow his instructions to have “the most pleasant afternoon together.” Steve asks participants to look around and see who else is participating. He asks participants take a deep breath.

- 4:00–4:30: Steve asks participants to stand up and wave to each other.