The most common way visitors participate with cultural institutions is through contribution. Visitors contribute to institutions by helping the staff test ideas or develop new projects. They contribute to each other by sharing their thoughts and creative work in public forums. Visitors contribute:

- Feedback in the form of verbal and written comments during visits and in focus groups

- Personal objects and creative works for crowd-sourced exhibits and collection projects

- Opinions and stories on comment boards, during tours, and in educational programs

- Memories and photographs in reflective spaces on the Web

Why invite visitors to share their stories and objects with the institution? Visitors’ contributions personalize and diversify the voices and experiences presented in cultural institutions. They validate visitors’ knowledge and abilities, while exposing audiences to content that could not be created by staff alone. When staff members ask visitors to contribute, it signals that the cultural institution is open to and eager for participation.[1]

Contributory projects are often the simplest for institutions to manage and for visitors to engage in as participants. Unlike collaborative and co-creative projects, which often accommodate only a small number of deeply committed and pre-selected participants, contributory activities can be offered to visitors of all types without much setup or participant coaching. These projects can function with minimal staff support; many are self-explanatory and self-maintaining. Contributory projects are also in many cases the only type of participatory experience in which visitors can seamlessly move from functioning as participants to audience and back again. Visitors can write a comment, post it on the wall, and immediately experience the excitement of seeing how they have contributed to the institution.

But contribution isn’t just for quick and simple activities. Contributory projects can also offer visitors incredible creative agency: to write their own stories, make their own art, and share their own thoughts. Consider the Denver Community Museum, a small, temporary institution that presented short-term exhibitions sourced solely from visitor-contributed content.[2] The founder/director, Jaime Kopke, posed a monthly “community challenge” for participants to create or bring in objects related to a specified theme. For example, challenge number five, Bottled Up! invited people to:

Fill a bottle with the memories of people and places from your life. Saved material can take any form – messages, objects, smells, sounds, photos – anything that shares your story. Multiple bottles welcome. Please decide if your bottle can be opened by visitors or if it should remain sealed.

The resulting exhibition displayed twenty-nine visitor-contributed exhibits: perfume bottles, pill bottles, wine bottles, and homemade vessels filled with evocative objects and images. Many participants designed their projects to be opened, allowing visitors to unfold secrets, take in smells, or discover hidden treasures. One young contributor was so excited that he returned to the museum every few days to rearrange his display of bottled toys and encourage visitors to play with his collection.

In addition to featuring pre-made visitor contributions, Kopke designed a simple interactive tree collage that hung on one gallery wall, holding open bottles with phrases like “First Love” and “Beliefs You Hold Sacred.” Visitors could write a memory on a slip of paper and add it to a bottle if desired. Kopke explained: “There was never an exhibit where the visitor simply viewed and read. The shows always included something that you could touch, take…or most importantly leave behind.”

Visitors to the Denver Community Museum enjoy “bottled up” exhibits contributed by community members of all ages. Photo by Jaime Kopke.

The Denver Community Museum was a small institution with no budget or paid staff. By respecting visitors and their ability to contribute, Kopke was able to provide unique audience experiences in which everyone felt like a participant or potential participant.

While few traditional institutions could be as completely contribution-driven as the Denver Community Museum, the same principle of respecting visitors and their contributions applies at even the largest institutions. In 2007, the Victoria & Albert Museum partnered with textile artist Sue Lawty to launch the World Beach Project, a contributory project with a very simple goal: to produce a global map of pieces of art made with stones on beaches.[3] The World Beach Project does not involve visitors coming to the Victoria & Albert Museum. It’s a project that requires people to do four things: go to the beach (anywhere in the world), make a piece of art using stones, photograph it, and then send the photos to the museum via the Web.

The World Beach Project website showcases beach artworks made by hundreds of participants all over the world. The project succeeds by combining an encouraging tone with respect for visitors’ unique contributions. Friendly, prominent statements on the website like, “it is really easy to join in” and “I want to add my beach project to the map” encourage inspired spectators to contribute their own work. The project values participants’ contributions by honoring the beach artworks as part of a commissioned work, accessioning them as collection pieces, and making them easy for visitors to explore.

Sue Lawty described the World Beach Project as “a global drawing project; a stone drawing project that would speak about time, place, geology and the base instinct of touch.” Lawty encouraged participants to think of themselves as part of a community of artists and a geologically connected ecosystem. The World Beach Project, like the Denver Community Museum, did not provide opportunities for trivial participation. These projects respected visitors’ creative abilities and provided engaging activities and platforms for their contributions.

Three Approaches to Contributory Projects

There are three basic institutional approaches to contributory projects:

- Necessary contribution, in which the success of the project relies on visitors’ active participation

- Supplemental contribution, in which visitors’ participation enhances an institutional project

- Educational contribution, in which the act of contributing provides visitors with skills or experiences that are mission-relevant

The Denver Community Museum and the World Beach Project are examples of necessary contribution. These projects could not exist without visitors’ active participation. In these projects, the goal of contribution is to generate a body of work that is useful and meaningful. Some necessary projects are helpful to staff because contributors generate data or research. Other necessary projects create new content for visitors to explore.

Participants often feel a high level of ownership and pride when their participation is tied to the project’s success. This pride doesn’t have to be individual; many contributory projects support a sense of shared ownership and community. One observer of the visitor-constructed Nanoscape sculptures at the Exploratorium appreciated the participatory approach “because anyone who comes could participate, and it makes people feel like they’re a part of things.”[4] No one contributor’s individuality stood out in the final assemblage of balls and sticks, but the collective power of the group experience made it a powerful participatory display.

When a contributory project relies on visitors’ contributions to succeed, it generates both high risk and high institutional investment. If participants don’t act as requested, the project can quite publicly fail, and there have been cases of video contests with just a couple of entries, or comment boards with one or two lonely notes. But fear of failure often also motivates staff members to put more thought and commitment into project design, so they can feel confident that visitors’ work will meet institutional needs.

For example, consider the experience of the exhibit developers at the Minnesota Historical Society who worked on the MN150 project. MN150 is a permanent exhibition of 150 topics that “transformed Minnesota.” It opened in 2007 to celebrate the 150th anniversary of the state’s founding.

The MN150 team decided to crowdsource the topics for the exhibition, reasoning that “it didn’t make sense” for a small group of developers and curators to decide which were the most important things to the residents of their large and varied state. Once they committed to this process, the team actively sought nominations from diverse residents by reaching out to leaders on Native American reservations, in small towns, and in immigrant communities. When an online call for topics brought in only a few nominations, staff members solicited people in other ways. They managed a booth at the Minnesota State Fair and hawked nomination forms cleverly designed as fans to encourage fairgoers to get out of the heat and contribute a topic. By the end of the nomination period, the staff had 2,760 nominations to sift through—more than enough to generate a high-quality exhibition that reflected the diverse opinions of Minnesotans.

The MN150 team encouraged people to contribute nominations to the exhibit at the state fair. The museum enticed people in with costumed historical interpreters, friendly staff, and an air-conditioned building. Photo courtesy Minnesota Historical Society.

Not every contributory project relies entirely on the participation of visitors. In supplemental contributory projects, the institution feels that visitors’ contributions, while not necessary, add a unique and desirable flavor to a project. Comment boards and “make stations” where visitors contribute artistic creations, are common forms of supplemental contribution. In supplemental projects, the goal is typically to incorporate diverse voices, add a dynamic element to a static project, or to create a forum for visitors’ thoughts or reactions.

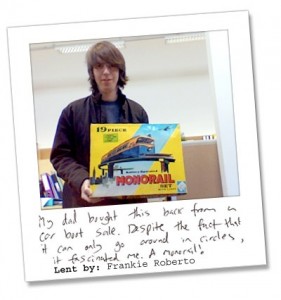

London Science Museum staff member Frankie Roberto contributed his own toy and story to Playing with Science’s participatory element.

When the London Science Museum displayed a temporary exhibition called Playing with Science about the history of science-related toys, the institution invited visitors to bring in their own toys on a few special weekends. Visitors’ toys were temporarily accessioned into the collection and displayed in a few vitrines at the end of the exhibition. Contributors were photographed with their favorite toy and wrote short statements about them, such as, “I play with this toy and pretend to be out in space,” or “I like making girls do boy parts because I am a tomboy.”[5] These visitor contributions personalized the exhibition and helped noncontributing visitors connect to the objects on display by triggering their own toy memories. It also introduced a dynamic element to an otherwise static historical display, thus supporting a light and evolving conversation among visitors, the institution, and the objects themselves.

Some people participate in supplemental contributory projects because they enjoy the momentary jolt of fame that comes from seeing their creation or comment on display. Others contribute to share a deeply felt sentiment or creative expression they feel driven to add to the evolving body of content. On many comment boards, sprinkled alongside the “John was here!” comments, you can read the impassioned arguments of visitors who loved, hated, or just wanted to discuss the exhibits on display. For example, the Pratt Museum’s exhibition Darkened Waters, opened in 1989 in reaction to the Exxon Valdez oil spill, featured comment boards and books that quickly filled with debate and discussion among visitors. Visitors often responded to each other’s comments or addressed the museum directly, feeling that even asynchronous conversation was valuable and necessary.[6]

If visitors become invested in dialogue about institutional content, it’s important for staff members to respond to and take part in the discussion. Supplemental projects suffer when they feel like afterthoughts. When institutions don’t need visitors’ contributions, the staff may not be as attentive to or respectful of visitors’ work. The best supplemental projects value visitors’ unique self-expression. Unlike projects of necessity, in which institutions often introduce constraints to ensure consistency of contributions, supplemental projects thrive when visitors are given license—and encouragement—to be creative or share strong reactions.

Finally, there are educational contributory projects initiated by institutions that perceive the act of contribution primarily as a valuable learning experience. I expect these types of projects to increase as more institutions place emphasis on participatory learning skills and new media literacies.[7] Most of these projects aim to teach skill building rather than generate content.

Visitors who enjoy trying and learning new things are particularly drawn to educational contributory projects. Considering their emphasis on hands-on learning and skills attainment, it is not surprising that science centers and children’s museums are most aggressively pursuing educational contribution. But participatory skill building can happen in history and art institutions as well. The Magnes Museum, a small Jewish art and history museum in Berkeley, CA, started the Memory Lab to invite visitors to contribute their own artifacts and stories to a digital archive of Jewish heritage.[8] While the emphasis is on “making memories,” Director of Research and Collections Francesco Spagnolo emphasized the concept that participants learn how to use digital tools to preserve, organize, and care for their own heritage. This contributory project, which is cast as a personal experience, supports skill building and appreciation for the ongoing work of the institution.

The Magnes Memory Lab succeeds because it invites visitors to explore their own family heritage, not to generally learn the skills of digitization. People are more receptive to learning new skills when they can clearly see how those skills are relevant to their own lives.

Asking for Contributions

Contributory projects thrive on simplicity and specificity. Generic requests for visitors to “share their story” or “draw a picture” are not as successful as those that ask visitors to contribute particular items under clear constraints. When institutions offer visitors compelling and understandable opportunities to contribute, many will enthusiastically participate.

From the participant perspective, a good contributory project:

- Provides specific, clear opportunities for visitors to express themselves

- Scaffolds the contributory experience to make participation accessible regardless of prior knowledge

- Respects visitors’ time and abilities

- Clearly demonstrates how visitors’ contributions will be displayed, stored, or used

CASE STUDY: How the Victoria & Albert Museum Asks for Contributions

The Victoria & Albert Museum’s World Beach Project has a particularly clear “ask” for visitors’ contributions. The website gives visitors a brief overview of the process:

The project happens in two stages, in two locations: first, at a beach where you choose the stones and make your pattern, recording the work-in-progress with some photographs along the way. Then later, at a computer, you can upload the photographs to this website to complete the project.[9]

This short statement is followed by step-by-step instructions that cover everything from finding a good beach to picking stones to sizing your photographs for submission to the site. The instructions provide encouragement for stymied artists, suggesting ways participants might sort or group beach stones to help plan their artworks. The instructions also assist less technologically-savvy participants by providing specific information about how to transfer photographs from camera to computer.

In the final submission process, each contributor is required to submit her name, the location of the beach, the year of the creation, a photo of the finished artwork, and a brief statement about how the work was made. Contributors can also optionally upload two additional photos: one of the beach and one of the work in process. Because the instructions explain everything that will be asked of participants, people are not surprised by any of the requirements.

The Victoria & Albert Museum provides contributors with legal terms and conditions explaining that they grant the museum a non-exclusive license to their contributed content. For savvy people—especially artists—such statements are necessary to make ownership rights clear and to promote mutual trust between participants and institutions.

The World Beach Project only solicits information that is needed to participate. Participants don’t have to register or share personal information to contribute. Email addresses are only used to correspond with contributors about their submissions. The staff respects the fact that people want to participate in the World Beach Project specifically and do not want to share their information.

When designing a contributory platform, it’s easy to be tempted by the desire to ask for more information or content from visitors. These requests come at a significant cost. Every additional question the institution asks puts a burden on participants. Keep it as simple as possible, and respect the fact that not everyone wants to share their contact information with their contribution.

Modeling Desired Participant Behavior

The easiest way to make contributors’ roles clear and appealing to would-be participants is through modeling. When a visitor sees a handwritten comment on a board, she understands that she too can put up her own comment. She takes cues from the length and tone of other comments. The models on display influence both her behavior and the likeliness of her participation.

Good modeling is not as simple as displaying representative contributions. The diversity, quality, and recency of the models, as well as the extent to which the platform appears “full” or “empty,” significantly impact whether newcomers participate.

Modeling Diversity

The greater the diversity of contributions in terms of content, style, and participant demographics, the more likely an approaching visitor will feel invited to contribute. Many museums with video comment kiosks provide only professionally-produced model content featuring celebrities or content experts. This is not conducive to participation. These models may successfully attract spectators who want to watch videos of celebrities sharing their views, but the production values and the type of people displayed send a clear message to visitors that their own opinions are secondary to expert or celebrity perspectives.

If you want to encourage people of all ages and backgrounds to share their thoughts, you should deliberately reflect and celebrate contributions from a range of people. For example, you might mentally “slot in” a model contribution from a child, in another language, or expressing a divergent viewpoint. Remember that not everyone shares the same definition of “high-value contributions.” Over-curating model content to feature only the contributions that please staff members will not motivate visitors with dissenting perspectives to participate.

In platforms like comment boards, where every new contribution is added to the model content, it’s important that visitors feel like the board is physically open to their contributions. No one wants to act alone and be under the microscope, but participants also don’t want to be lost in the crowd. We all intuitively know the difference between a conversation that feels open to our opinion and one that is already overcrowded with voices. Platforms that have explicit “slots” for content on display, such as comment boards or video kiosks that display grids of videos, can overwhelm and discourage continued participation when the slots appear to be all filled up.

One easy way to solve this problem is to give each new participant a clear position of privilege in the map of contributions to date. In exhibits that invite visitors to add their own personal memories via sticky notes onto maps or timelines, this position of privilege is self-evident. The newest layer of notes lies on top of older ones, giving participants confidence that their story will be read, at least for a while. In digital environments, or ones in which staff is in control of the presentation of contributions and model content, it is useful to provide visitors with an obvious “pathway” or slot for their contribution, so they can see where it will go visually and physically.

In physical environments in which visitors can display their own objects or creations, you may want to set a general rule for how much space will be kept open for new contributions. At the shoe-making station in the Ontario Science Centre’s Weston Family Innovation Centre, the staff has settled on keeping one-third of the showcase space open for new visitors’ handmade shoes at any time. Generally, a platform that has one-fourth to one-half of the space open provides a feeling of welcome and encourages visitors to share.

If you want to organize contributions using criteria other than recency, you can create explicit areas of a comment board or contributory platform for different kinds of participants. Labels with text like, “Where does your opinion fit into the conversation?” or “Place your creation near others that you feel are connected” can help visitors feel that there is a place for their unique participation, no matter how crowded the field.

Modeling Quality

While diverse models encourage visitors to participate, high-quality models inspire them to take contribution seriously. The most powerful model content is diverse, high-quality, and ideally, produced by “visitors like you.” Superlative visitor creations are exciting and attractive, and people can identify with them more easily than they do with celebrity or staff-created content. Visitor-created models demonstrate how non-professionals can use the materials offered to create something of value.

High-quality model contributions can inspire and energize less-skilled visitors without making them feel inferior. For example, I am lousy at drawing, but like most people, I’m attracted to well-rendered sketches. When I see poorly-made drawings in a visitor-created exhibit, I’m never motivated to pick up crayons and start coloring. But when I see something really unusual, surprising, or appealing, I’m more likely to be intrigued by the experience overall, which may inspire me to participate as well.

Superlative visitor contributions make good models because they were created using the same tools available to every visitor. When institutions choose to feature celebrity or staff-produced model content, those contributions should be created using the same materials available to visitors. If visitors will write in crayon, staff members and celebrities should write in crayon.

This principle extends to entire exhibitions. In the best contributory displays, the tools available for contribution match those used by designers and curators elsewhere in the exhibition, so that visitors’ contributions blend attractively into the overall display. This promotes respect and value for visitors’ contributions. It also helps visitors naturally extend their emotional and intellectual experience of the exhibition to their contributions. Asking visitors to jump from a dimly lit, immersive display to a sterile comment book can be jarring. Inviting them to continue their experience in a well-designed contributory platform helps smooth the transition from spectating to participating.

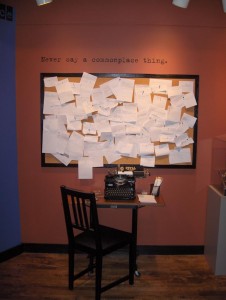

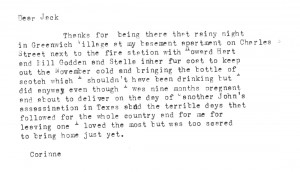

This technique was very powerfully employed in a 2007 exhibition of Jack Kerouac’s original typewritten manuscript for the beat masterpiece On The Road at the Lowell National Historical Park in Massachusetts. Alongside the iconic manuscript, the exhibition featured a talkback area in which visitors could contribute their own reflections. Instead of offering sticky notes and pens, the staff provided a desk with a typewriter (amazingly, donated by the Kerouac family) and an evocative quote from Kerouac: “Never say a commonplace thing.” Visitors responded enthusiastically, generating over 12,000 messages at the typewriter in six months. Several wrote letters directly to Jack. Some wrote poems. The integrated design of the space invited visitors to extend their personal, emotional experience with the artifact to the comment station. This produced a powerful collection of visitor-contributed comments that enhanced the exhibition overall.

The visitor comment station for On the Road allowed visitors to stay in the emotional space of the exhibition while sharing their thoughts. Photo courtesy Lowell National Historical Park.

One of many touching visitor comments shared at the On the Road comment station. Photo courtesy Lowell National Historical Park.

Novice Modeling

Sometimes, the best way to encourage people to participate in new and potentially unfamiliar settings is by providing novice models. When staff members or professionals present themselves as amateurs, it helps people build confidence in their own abilities.

One of the best examples of novice modeling is the National Public Radio show RadioLab. RadioLab features two hosts, Robert Krulwich and Jad Abumrad, who explore broad science topics like “time” and “emergence” from a variety of scientific perspectives.[10] Commenting on their process at an event in 2008, Krulwich said:

We don’t know really what we’re talking about at the beginning—we find out along the way. And we make that very clear. So we never pretend to anybody that we’re scholars ‘cause we’re not. And we do represent ourselves as novices, which is a good thing. It is a good thing in a couple of ways. First, it means we can say, “what?!” honestly. And the second thing, “can you explain that again?” honestly. And then the third thing is, it allows us to challenge these people as though we were ordinary, curious folks. We’re trying to model a kind of conversation with important people, powerful people, but particularly knowledgeable people, where we say—YOU can go up to a person with a lot of knowledge and ask him “why?,” ask him “how does he know that?” Tell him, “stop!” Ask him why he keeps going. And get away with it. And that’s important.[11]

RadioLab isn’t just a show where the hosts have conversations with scientists. It’s a show where the hosts model a way for amateurs to have conversations with scientists and engage with experts rather than deferring to or ignoring them.

To do this kind of modeling, Krulwich and Abumrad actively portray themselves as novices. They make themselves sound naive so listeners don’t have to feel that way. By humbling themselves, they create a powerful learning experience that promotes accessibility and audience participation.

Modeling Dynamic Participation

Visitors notice whether model content on contributory platforms is up-to-date. Recency of model content signals how much the staff cares for and tends to contributions. Imagine an exhibit that invites visitors to whisper a secret into a phone and then listen to secrets left by other visitors. If the secrets they hear are several months old, visitors may have less confidence that their own secrets will soon be made available to others.

When institutions promise, explicitly or implicitly, that visitors’ contributions will be on display, visitors want immediate feedback that tells them when and where their work will appear. Whenever possible, they want it to be on display right away. If participants choose to contribute to a community discussion, they don’t want to put their comments into a queue for processing—they want to see their words join the conversation immediately. Automatic display confirms that they contributed successfully, validates them as participants, and guarantees their ability to share their work with others.

Some projects motivate participation by displaying current contributions in compelling and desirable ways. For example, the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum’s From Memory to Action exhibition features a pledge station and display wall. Visitors can sit at the stations and scrawl their promises of actions they will take “to meet the challenge of genocide” on special digital paper with pens. The paper is perforated with one section about the exhibit and web presence, which visitors keep, and another section for the promise, which visitors leave at the museum.[12] Visitors drop their signed pledges into clear plexiglass cases that are beautifully lit. The paper “remembers” the location of pen marks on the pledge section, so visitors’ handwritten promises are immediately, magically projected on a digital projection wall in front of the pledge kiosks.

This pledge wall is a beautiful demonstration of how the aesthetic and functional design of contributory platforms can be mutually beneficial. Why require visitors to hand-write their pledges rather than typing them in on a keyboard? It certainly would be easier for the museum to digitize and project visitors’ entries if they were typed, and it wouldn’t require so much expensive digital paper. But asking visitors to hand write a response and sign a pledge ritualizes and personalizes the experience. Adding their slips of paper to the physical, growing, and highly visible archive makes visitors part of a larger community of participants. Taking home the bookmarks reinforces their connection to the contributory act and inspires further learning.

Visitors make their handwritten pledges facing a projection screen which magically “rewrites” their promises digitally when they drop them in the slots. Photo by U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum/Max Reid.

The case full of signatures and the digital animations of the handwritten pledges provide a captivating and enticing spectator experience. The case full of visitors’ signatures is reminiscent of the haunting pile of Holocaust prisoners’ shoes in the permanent exhibition, providing a hopeful contrast to that devastating set of artifacts. The combination of the physical accumulation of the paper stubs and the changing, handwritten digital projection reflects the power of collective action and the importance of individual commitments.

There are far more visitors who spectate in From Memory to Action than actively contribute. Curator Bridget Conley-Zilkic noted that in its first eight months, about 10% of people who visited chose to make a pledge in the exhibit. However, about 25% of visitors picked up a pledge card. As Conley-Zilkic reflected, “There’s an awkward moment where people want to think about it—they aren’t necessarily immediately ready to share a pledge on such a serious topic.” For these visitors, picking up a card is a way to express interest in the experience. Not everyone needs to contribute on the spot to participate.

Curating Contributions

There’s a big difference between selecting a few contributions to model participation for visitors and putting all contributed content on display. When visitors’ creations are the basis for exhibits, comment boards, or media pieces, the questions of whether and how to curate contributions comes up.

Curation is a design tool that sculpts the spectator experience of contributory projects. If institutions intend to curate visitors’ contributions, the staff should have clear reasons and criteria for doing so.

There are two basic reasons to curate visitor-generated content:

- To remove content that staff members perceive as inappropriate or offensive

- To create a product that presents a focused set of contributions, such as an exhibition or a book

Removing Inappropriate Content

One of the most frequent concerns staff members voice about contributory platforms is the fear that visitors will create content that reflects poorly on the institution, either because it is hateful or inaccurate. Fundamentally, this concern is about loss of control. When staff members don’t know what to expect from visitors, it’s easy to imagine the worst. When staff members trust visitors’ abilities to contribute, visitors most often respond by behaving respectfully.

On the Web, people who make offensive comments or terrorize other users are called “griefers.” Fortunately, few museums suffer from participants who use contributory platforms to actively attack other visitors. Cultural institutions already have developed ways to deal with griefers of a different type—the ones who vandalize exhibits and disrupt other visitors’ experiences. When it comes to people who want to vandalize the community spirit, the same techniques—proactive staff, model users, and encouragement of positive and respectful behavior—can prevail.

There are also many ways to block curse words in particular. One of the most creative of these was created by the interactive firm Ideum for a comment station in The American Image exhibition at the University of New Mexico museum. Ideum automatically replaced all curse words contributed with cute words like “love” and “puppies,” which made inappropriate comments look silly, not offensive.

There are also intentional design decisions that can persuade visitors to behave well. At the Ontario Science Centre, the original version of the Question of the Day exhibit featured two digital kiosks on which visitors could make comments that were immediately displayed on overhead monitors. The staff quickly observed that young visitors used the kiosks to send off-color messages to each other rather than to comment on the exhibit question. They removed one kiosk, which ended the offensive conversations, but the remaining kiosk continued to draw off-topic content related to body parts. Then staff moved the kiosk to a more central location in front of the entrance to the women’s bathroom. Once it was placed in the proximity of more visitors (and moms in particular!) the bad behavior on the kiosk dropped significantly.

Staff members need not be the only ones who moderate contributions. Visitors can also be involved as participants in identifying inappropriate comments. Many online contributory platforms allow users to “flag” content that is inappropriate. A “flagging” function allows visitors to express their concerns, and it lets staff focus on reviewing the content that is most likely to cause controversy rather than checking every item.

Some staff members are less concerned about curse words than inaccuracies. If a visitor writes a comment in a science museum about evolution being a myth, or misidentifies a Degas as a Van Gogh in an art institution, other visitors may be exposed to content that the institution does not officially sanction. This is not a new problem; it happens in cultural institutions all the time. Tour guides, parents, and friends give each other misinformation as they wander through galleries. The concern is that when this misinformation is presented in contributory exhibits, visitors may be confused about its source and incorrectly attribute it to the institution.

There are several ways to address inaccurate visitor contributions. Staff may choose to actively curate all submissions, checking them for accuracy before allowing them to be displayed. Other institutions take a “yes, then no” approach, moderating contributions after they have been posted or shared.

There are also design strategies that address the issue of accuracy by clearly identifying which contributions are produced by staff or institutional partners and which created by visitors. For example, on the Museum of Life and Science’s Dinosaur Trail website, comments are color-coded by whether the author is a paleontologist (orange) or a visitor (yellow).[13] This subtle but easy-to-understand difference helps spectators evaluate the content presented.

Curating an Audience-Facing Display

There is a fundamental difference between contributory projects that promote community dialogue and sharing and those that produce a highly-curated product. If your goal is to validate visitors’ voices or encourage conversation, the curatorial touch should be as light as possible. Spend your design time focused on how to display the contributions so they work well together rather than trying to select the best for display. The Signtific game is a good example of this (see page 122). Instead of developing a curatorial or monitoring system, the designers developed ways to explicitly require players to respond to each other and build arguments together, so that every new voice had a place in the growing conversation.

Even inconsequential visitor comments are important to include when your goal is visitor empowerment. When people write on each other’s walls on Facebook, they are often just saying hi and asserting their affinity for the other person or institution. The same is true of the people who write, “Great museum!” in comment books in the lobby. These statements are a form of self-identification, and while they may not make very compelling content for audiences, the act of expression in a public forum is important to those who contribute their thoughts, however banal.

If your goal is to create a refined product for spectators, however, you may opt for a more stringent set of curatorial criteria. Phrases like “contribute to the exhibition” as opposed to “join the conversation” can help signal to visitors that their work may be curated.

There are many contributory art projects that only display a small percentage of contributions received. Frank Warren of PostSecret (see page 156) receives over a thousand postcards weekly from contributors all over the world, but he curates the postcards very tightly for public consumption, sharing only twenty per week on the PostSecret blog. PostSecret could easily devolve into a display of prurient, grotesque, and exaggerated secrets, but Warren’s curatorial touch only puts cards with authentic, creative, diverse voices on display. Other artist-run projects, like the Museum of Broken Relationships,[14] which collects and displays objects and stories related to breakups, employ an invisible curatorial hand to maintain a consistently high-quality spectator experience, even as it receives unsolicited and unexhibited submissions on a continual basis.

Curation policies don’t just impact how the staff uses visitors’ contributions. They also serve as an important opportunity to demonstrate respect for participants and provide feedback. When visitors create something and then drop it into a box for staff review, they entrust their work into institutional hands. Visitors want to know how contributions will be evaluated, how long it might take, and whether they will be notified if their contribution is included in some audience-facing display. This doesn’t need to be exhaustive. A sign that says, “Staff check these videos every week and select three to five to be shown on the monitor outside. We are always looking for the most creative, imaginative contributions to share” will help visitors understand the overall structure and criteria for contribution.

Very few institutions get back in touch with visitors to let them know that their content is being featured, but doing so makes good business sense. It’s a personal, compelling reason for the institution to contact people who may not have visited since making their contribution, and it’s likely to bring them back to show off their creation to friends and family.

Audience Response to Contributory Projects

There is a wide audience for contributory projects in cultural institutions. Participants, spectating visitors, stakeholders, and researchers may all use contributed content. When thinking about how to design platforms for contribution, it’s important to consider not only what will motivate people to share their thoughts, but what will entice, inspire, and educate visitors who choose to read or observe others’ contributions.

Making Contributory Projects Beautiful

One of the challenges of integrating contributory platforms into cultural institutions is the perception that comment boards and visitors’ artistic creations are not as attractive to spectators as institutionally-designed material. However, it is possible to make even the most mundane visitor contributions beautiful. In the late 2000s, manipulatable data visualizations became ubiquitous on the Web, and people enjoyed fiddling with everything from data on baby names to crime statistics to the frequency of different phrases in internet dating profiles. From an audience perspective, playing with visitor-submitted data can be a comparably fun and attractive way to explore vast sets of contributions while learning important analytical skills. Even the simplest visualizations, such as the LED readouts above the turnstiles in the Ontario Science Centre’s Facing Mars exhibition (see page 97), let audiences learn from, enjoy, and engage with visitor-submitted content.

CASE STUDY: Making Visitors’ Comments an Art Experience at the Rijksmuseum

In 2008, the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam hosted Damien Hirst’s piece For the Love of God, and with it, a visitor feedback system that provided a striking and attractive spectator experience. The artwork was a platinum-cast skull encrusted with over 1100 carats of diamonds: a hype machine in death’s clothing. It was mounted in a dark room, surrounded by guards and beautifully lit. Nearby, visitors who wished to provide feedback on the skull could record videos in small private booths.

The For the Love of God website transformed the contributed videos into an interactive online experience.[15] The videos were automatically chromakeyed (i.e., masked or cropped) so that each contributor appeared as a floating head, which created an eerie, appealing visual consistency. The heads drifted around an image of the skull, and spectators could sort the videos by country of origin, gender, age, and some key concepts (love it, hate it; think it’s art, think it’s hype). Click on a head and the video made by that visitor popped up. After it played, it faded back into the floating mass.

The For the Love of God website was couched in the same self-conscious buzz that permeated the exhibit. A welcome screen informed visitors: “Never before has a work of art provoked as much dialogue as Damien Hirst’s For the Love of God.” Whether true or not, the website implied that the contributed videos were a justification for this claim, a demonstration of the rich dialogue supposedly surrounding the skull. In this way, the visitors’ videos were integrated into the larger artwork as part of the skull experience. The audience experience of the feedback contributions was immersive, intriguing, and haunting—like that of the skull itself.

Visitor Reactions to Contributory Exhibitions

How does the experience of exploring visitor-contributed content differ from consuming standard exhibits or museum content? Just as a diverse blend of contributions can motivate people to participate in contributory platforms, audience members may feel more personally included in the institution when they see “people like them” represented.

In 2006, the Art Gallery of Ontario (AGO) developed In Your Face, an exhibition of 4×6 inch visitor-submitted self-portraits. Over 10,000 self-portraits were submitted, and the portraits hung in an overwhelming and beautiful mosaic, blanketing gallery walls from floor to ceiling. Toronto is a very culturally diverse city, and Gillian McIntyre, coordinator of adult programs, noted, “The portraits noticeably reflected far more diversity of all sorts than is usually seen on AGO walls.” She shared:

On several occasions children in visiting school groups from West and East Indian communities enthusiastically pointed out people who looked like them on the walls, literally saying, “That looks like me” or “That’s me with dreadlocks.”[16]

The exhibition was incredibly popular, attracting significant crowds and media attention. Visitors saw themselves in the exhibition in a way they never had before. Another visitor even took the experience from personal to collective, commenting: “it’s depicting the soul of a society.”

MN150 had a similar effect on visitors, despite being a much more conservative installation. Unlike In Your Face, MN150 was not a direct installation of visitor contributions. Instead, it displayed the distillation of 2,760 visitor nominations into 150 fairly consistently designed exhibits about the history of Minnesota. Each exhibit label included the text contributed in the original nomination form, as well as a photo of the nominee. But otherwise, with a few exceptions in cases where nominees provided objects, the exhibits were designed and produced by staff in a traditional process.

In summative evaluation of MN150, very few visitors commented on the user-generated process that created MN150 but many saw the exhibition as both personally relevant and diverse in content. When asked “What do you think the museum is trying to show in the overall Minnesota 150 exhibit?” visitors frequently talked about the diversity of people and events represented in the exhibit, as well as their own state pride. They also related individual exhibits readily to their personal experiences, sharing memories from well-known places and events. One person commented that “her husband would love the exhibit. She would tell him, ‘Here is your life.’”

Anecdotally, staff noted that the video talkback station in MN150 was particularly active. The kiosk invited visitors to make their case for other topics that should have been included in the exhibition. The display of visitors’ voices throughout the exhibition likely made audience members feel that there was more room for their own opinions than in a typical exhibition. The Art Gallery of Ontario’s In Your Face exhibition had a similar effect, with many more visitors than was typical visiting a station where they could make their own portraits inspired by those on display. Exhibitions of visitor-contributed content can inspire new visitors to participate in related but not identical ways to the original contributors.

Alongside the exhibition of visitor-contributed portraits in In Your Face, there were popular activity stations where visitors could look in the mirror and draw their own self-portraits. Photo (c) Art Gallery of Ontario 2007.

Does the Contributory Process Matter to Audiences?

Summative evaluation revealed that MN150 visitors didn’t express strong reaction to the contributory process that had created the exhibition. Yet their comments about the exhibition, and the social and participatory nature of the visitor experience, reflected the impact of that process. Visitors saw the exhibition as diverse, multi-vocal, and personal—all outcomes of an approach that celebrated the unique voices of 150 Minnesotans from across the state.

Audiences focus on the outcome, not the process that created it. Contributory processes generate outcomes that are different from those generated by staff alone. The staff could not have drawn the portraits shown in In Your Face that helped underrepresented visitors “see themselves” in the Art Gallery of Ontario. They could not have written the raw letters and poems that emerged from the typewriter in On the Road. They could not have created the silly labels that made the Odditoreum (see page 178) playful and fun.

Visitors are not only looking for the most authoritative information on a given topic. Visitor-contributed content is often more personal, more authentic, more spontaneous, more diverse, and more relevant to visitors’ own experiences than institutionally designed labels and displays. Visitor-contributed content does not produce intrinsically better audience experiences than institutional-designed content. But many cultural professionals are unwilling or unable to produce content that is as raw, personal, and direct as that which visitors create. Hopefully, working with and seeing the positive impact of visitor-contributed content will give more institutions the confidence to transform the way they create and display content.

***

Contribution is a powerful model for institutions that have a specific time and place for visitors’ participation. Some institutions want to engage with visitors in more extensive partnerships, inviting participants to help co-design new exhibits or projects. If you are looking for ways for people to contribute to your institution in more varied ways over a longer timeframe, you may want to consider shifting to a collaborative approach. That’s the topic of Chapter 7, which describes the why and how of collaborating with visitors.

Chapter 6 Notes

[1] For an excellent list of the benefits of visitor contribution, consult Kathleen McLean and Wendy Pollock’s introduction to Visitor Voices in Museum Exhibitions, ed. McLean and Pollock (2007).

[2] Learn more about the Denver Community Museum in Jaime Kopke’s December 2009 blog post, Guest Post: the Denver Community Museum.

[4] See Erin Wilson’s article, “Building Nanoscape,” in Visitor Voices in Museum Exhibitions, ed. McLean and Pollock (2007): 145-147.

[6] See Mike O’Meara’s article, “Darkened Waters: Let the People Speak,” in Visitor Voices in Museum Exhibitions, ed. McLean and Pollock (2007): 95-98.

[7] See Chapter 5 for more information about participatory learning skills and new media literacies.

[11] Hear Krulwich and Abumrad talk about their approach in this audio segment (the quoted section occurs at minute 15).

[12] In the original design, visitors were instructed to take their pledges home, but the staff quickly discovered visitors wanted to leave them at the museum. They adjusted the cards’ design so visitors take home a bookmark and leave their pledges.

[14] Explore the virtual Museum of Broken Relationships.

[16] Read Gillian McIntyre’s article, “In Your Face: The People’s Portrait Project,” in Visitor Voices in Museum Exhibitions, ed. McLean and Pollock (2007): 122-127.